Earlier this week, my town experienced a police-involved killing, and an elected representative of the community was on the scene shortly afterward. He told reporters he did not want to repeat he-said/she-said but was awaiting video and other evidence: “My job is to get the facts – what happened.”

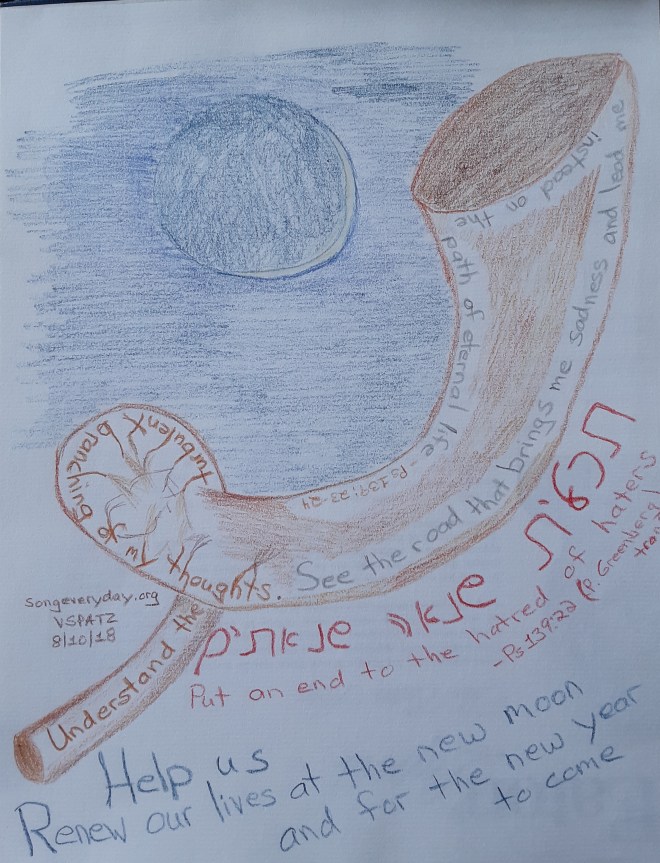

I’m sure many readers know or can guess the specifics, but I’m leaving them out because I think this situation, like the tale of Korach and his followers — a narrative, which Jews read this week in the annual Torah cycle (Numbers 16:1-18:32), about community and power — has something more universal to teach.

The Official Job

My first thought on hearing this official say his job was to “get the facts” was: No, that’s the job of police detectives and journalists; your job is legislative, budgetary, and related responses to the town’s many challenges. I realized immediately, however, that my first thought came from a fantasy world.

Leaving the facts to journalists and police only works in a world where community members can rely on those individuals and their institutions to pursue the full story, where some level of trust exists.

Officials from some other parts of town have the luxury of sticking to the duties for which they were elected, the privilege of living and working where basic systems appear to be functioning — at least for the people they represent. In the hugely unlikely event that a police-involved killing (God forbid any more anywhere) were to arise on the streets of some other districts in town, elected representatives and constituents could continue their own work, while expecting investigative professionals to do theirs.

This particular official, however, operates amid systems which have long since ceased to function for too many of the people he represents.

So, what exactly is his job? Can it possibly be similar to those of his official colleagues?

The Rebellion

In the bible story, Korach and his followers accuse Moses and Aaron of exalting themselves over the congregation of God. Although teachers over the centuries have made efforts to find some merit in Korach’s argument, he remains the poster child for the evils of greed, self-aggrandizement, and self-interested politics.

We also read that Dathan and Abiram call Moses unfit to lead the People, given that his leadership has already resulted in them being condemned to die in the wilderness (Num 16:13). Just a few chapters earlier, God announced a punishment, following the incident of the spies, for all the adults: “your carcasses shall drop in this Wilderness. Your children will roam for forty years and bear your guilt…” (Num 14:32-33).

The argument from Dathan and Abiram fares no better, in the bible narrative, than Korach’s initial challenge, and the result is catastrophic:

So Moses stood up and went to Dathan and Abiram, and the elders of Israel followed him. He spoke to the assembly, saying, “Turn away from near the tents of these wicked men, and do not touch anything of theirs, lest you perish because of all their sins.” So they got themselves up from near the dwelling of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram, from all around….

When he finished speaking all these words, the ground that was under them split open. The earth opened its mouth and swallowed them and their households, and all the people who were with Korach, and the entire wealth.

— Num 16:26-27, 31-32

Things go from bad to worse in the bible story, and the Children of Israel eventually tell Moses: “Behold! we perish, we are lost, we are all lost….Will we ever stop perishing?” (Num 17:27-28)

Our Job

Every year when we come to this Torah portion, I find myself worrying about the failures of communication involved in the rebellions and wondering how differently things might have evolved, given better listening.

Why are Moses and Aaron, and God, so surprised and unhinged by the People’s lapse of faith (in the spies incident, previous portion)? What if God had just heard their worries instead of responding so negatively to their hesitation?

Why are Moses and Aaron, and God, unable to hear the people’s desperation and anger, in the face of completely failed expectations?

And what is our job, as community members — and, if appropriate, as Jews — whether we live in an area suffering from severe system break-down or not? How might better listening, and closer attention to circumstances behind complaints and rebellion, change things?