The Torah reading calendar, in these early weeks of 2026, brings turmoil, oppression, distrust of leadership, and all kinds of violence to the environment and to humans. The first four portions of the Book of Exodus (chapters 1-17) lead us from one form of uncertainty and distress to another…. Not unlike the news, most years, with 2026 working harder than usual to parallel the text…. Meanwhile, the overall Exodus story appears to applaud a turbulent upheaval, one with unacknowledged trauma for everyone involved. Yet, through it all, Torah in these weeks also calls forth healing and possibility….

Story

Decades ago, Michael Walzer concluded Exodus and Revolution with this adage about “what the Exodus first taught,” which has since found its way into countless essays, sermons, and Passover readings:

“…first, that wherever you are, it is probably [Mitzrayim]; second, that there is a better place, a world more attractive, a promised land; and third, that the way to the land is through the wilderness. There is no way to get from here to there except by joining together and marching.” — Exodus and Revolution (Basic Books, 1985)

This perspective is still pretty common. But some voices, like that of Aurora Levins Morales, have been calling instead for a view that insists: “We cannot cross until we carry each other / all of us refugees, all of us prophets….This time it’s all of us or none.” And I am still among those looking for yet another way to read the Exodus story so that there’s no need of violent parting of people at all: Isn’t there a possible future in which all the people suffering from tyranny get out from under and build something better that uplifts all?

Last year (5785/2025), for the season between Passover and Shavuot, I explored ideas relating Passover to Sefer Yetzirah (the Book of Creation) and to dance, or “following in someone’s footsteps,” as the creative heart of the Exodus story. This year, these pre-Passover weeks are leading me back to dance in the Exodus story.

Movement

Dr. Anathea Portier-Young teaches about movement and the Exodus story:

- at the end of 430 years, the people go out [ yatzu, יָצְאוּ ] from Mitzrayim, Ex 12:41;

- Miriam leads and the women go out [ vateitz’an, וַתֵּצֶאןָ ] in dance, Ex 15:19-21;

- the people go out [ vayeitzu, וַיֵּצְאו ] into the wilderness, Ex 15:22;

- in addition, the people are in motion — walking, coming through, crossing — in many spots, such as Ex 14:16, Josh 4:22; Neh 9:11; Ps 66:6.

Exodus is movement, Portier-Young says, and “God is the one who sets the people in motion…” The covenant is not just celebrated through movement, including dance, but shaped by it: “…God’s and the people’s very being — identity, awareness, and capacity for action in relation to one another — these take shape in the dance.” (from her 2022 lecture)

Portier-Young also focuses on the healing role of dance, with particular reference to the dance in Exodus 15: “Their bodies carry the memory of enslavement, state violence and terror, and maternal bereavement….their dancing enacted freedom in community, awakened bodily memory and knowing, and created opportunity for integration, connection, and healing” (from her 2024 paper; more on her teaching in text and lecture).

Moment

Practice:

In a recent exploration of the portion Bo (Ex 10:1-13;16), R’ Yael Levy, A Way In: Jewish Mindfulness, noted the portion opens in the midst of “raging plagues” and “hardened hearts,” brutality and cruelty: there is no getting around that the liberation of this story “comes through hardship and pain.” So, R’ Yael asks: “Can we begin to do this differently? How do we meet the onslaught of violence?” She suggests this practice:

The portion opens with God saying, “Come [bo].” This seems to be telling us, R’ Yael says, to move toward God, to be found, already, in the mess: “…the devastation and chaos and turmoil that is the result of a hardened heart, to seek healing somehow, here, in this place….” We can approach the news and the needs around us by sending out rachamim/compassion to those in need, thus seeking to fill the world with more compassion, and seeking to ensure that our own hearts are not hardened (Torah Study for Bo — A Way In Torah studies are available on SoundCloud)

Vision/Prayer:

Discussing the portion Beshalach (Ex 13:16-17:16) this week, World to Come Twin Cities talked about exhaustion in the midst of trauma, the need for healing — in the story, in the congregation’s home cities, and in the wider world today — and the way God and the people seem to be learning together about human needs and how to meet them: “Oh you’re hungry? Oops! I guess you-all do need food,” God seems to be stumbling toward awareness in Chapter 16.

Reflecting on the manna introduced after the people’s complaints, one participant envisioned places in crisis having simple needs met, such as “bread for everyone, every day, for as long as needed,” so folks can heal and figure out what’s next. (WTCTC Torah study is virtual and open to all interested).

New Year

R’ Lauren Tuchman teaches many places and posts at “Contemplative Torah.” One of her recent teachings focuses on the New Year for Trees (Tu B’shvat, Feb 1, 2026). In the northern hemisphere, where Judaism began, this holiday is celebrated while the ground is still frozen and trees are not apparently thriving. So, R’ Lauren says, Tu B’Shvat is a reminder that “the future is undetermined, possibility exists, even when we cannot see it, touch into it, feel it, sense it in some way…”

These days, R’ Lauren adds, “there is a lot of despair and a lot of feeling like we have no idea what’s coming, what the future will hold. We cannot imagine the possibility for an abundant, co-creative future. It’s almost as if our spiritual imagination has been cut off at the roots. Tu B’shvat offers us an opportunity to re-root ourselves, to re-root ourselves in our own soil, to water ourselves, to care for ourselves. …. can we trust that blossoming will happen?”

This particular teaching is open to subscribers (paid and unpaid subscriptions available). A related teaching on the portion Beshalach is available at My Jewish Learning:

“…On the other side of the Reed Sea, the Israelites find a wilderness without sustenance; the people collectively crash. Overcome by fear and hunger… they would rather have died enslaved but sated than starving in this place of scarcity. When we feel a sense of destabilization in our own bones, as our ancestors did, we too have to slow down and intentionally take in all that surrounds us that is nourishing, supportive, even when the world around us is replete with tremendous challenge.” — R’ Lauren Tuchman, “Manna for the Soul“

Story, Moment, and Movement for THIS YEAR

As we continue through Exodus readings and pause to celebrate Tu B’Shvat, this particular year, perhaps we can move toward some new co-creative, intra-actional ways of approaching the story. We cannot overlook the violence and trauma and uncertainty in the story, but we need not be stuck there; the Exodus story also contains seeds of healing:

- it’s also about listening to one another needs;

- it’s about bread for everyone and noticing where there is sustenance;

- it’s about doing what we can, in the midst of confusion and violence;

- it’s about bringing rachamim/compassion into the world and avoid more hardening of hearts;

- it’s about possibility at an impossible time;

- it’s about using our bodies

And, perhaps, like Miriam with her dance, we can use our bodies in new ways — refugees, prophets, divinity together — to reshape it the Exodus story and our futures in the retelling.

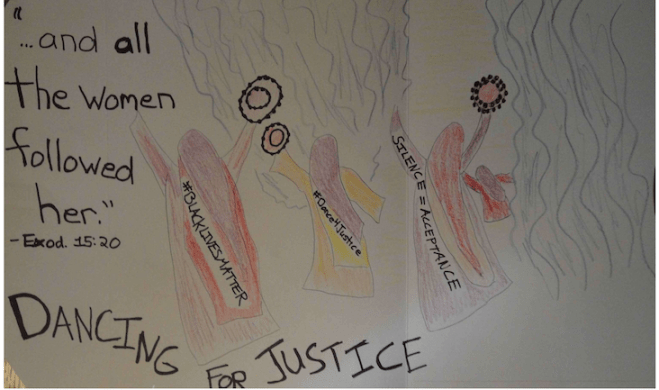

“Dancing for Justice” poster created for informal Black Lives Matter action in 2015 and given to the organizer at the time.

Alt Text: “DANCING FOR JUSTICE” amateur colored-pencil drawing: robed figures with raised timbrels, some of whom are labeled: #BlackLivesMatter, #Dance4Justice, and Silence=Acceptance. Larger text reads: “…and all the women followed her.” — Exod 15:20