NOTE: In conjunction with this dvar torah, I produced a four-page set of background materials. For the purposes of this post, I added hyperlinks to all sources not directly quoted in the dvar proper. But the source sheet was actually designed to stand as its own, so it might prove useful to download the PDF as well: Ki Teitzei sourcesheet (PDF)

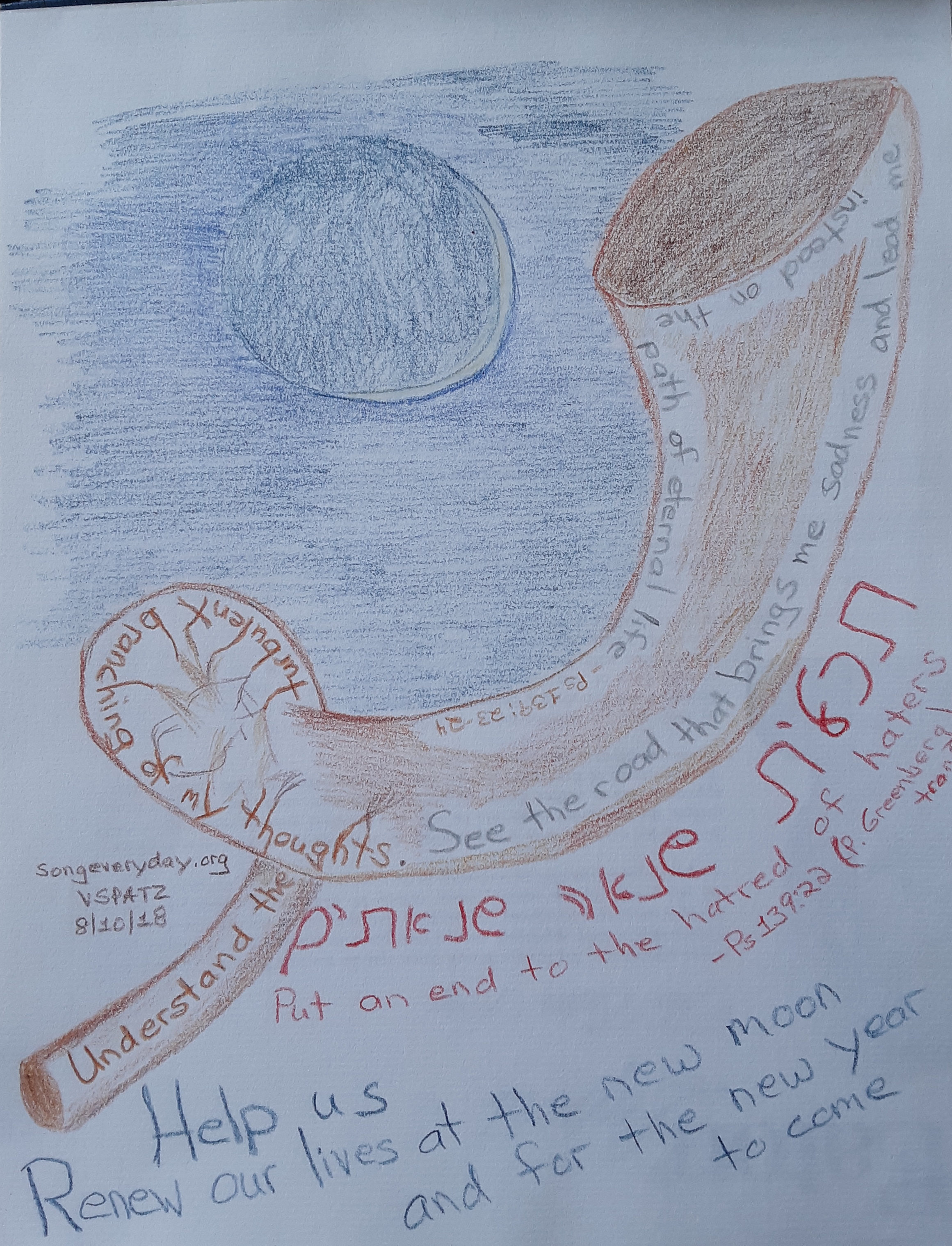

I learned something in preparing for this week’s portion that changed my perspective on several things, and I hope I can convey it in a way that at least makes sense and maybe also gives you a new way to look at some things. I prepared a source sheet with bits of Torah, later parts of the Hebrew bible, notes from Talmud, medieval and later writings. We’re not going to follow the material in order, and I know it’s a lot to ask, but I’m hoping you’ll be willing to follow me on a somewhat meandering path. As it says in one of my favorite Grateful Dead songs:

Once in a while you get shown the light

In the strangest of places if you look at it right.

— Scarlet Begonias, Hunter/Garcia 1974

Ki Teitzei and Commandments

We’ll start with a few words about this week’s portion. It contains a wide range of commandments. Some I think most of us would agree are sensible, kind and just: building houses so as to prevent accidents, returning lost property, and paying promptly for hired work. A few – like not wearing mixtures of linen and wool – are so hard to explain that they’re often put into the category of decrees to follow even if we don’t know why. Several are quite disturbing, like an order to obliterate whole peoples and a commandment to bring a rebellious child to the town elders to be killed.

All these commandments – the worrisome, the crazy-sounding, and the easy to accept – have been the subject of thousands of years of discussion and the source of many ethical directives, as well as mystical teachings, sometimes both woven together. This portion is one that reminds us that

- A) Jewish tradition rarely, if ever, accepts a text entirely at face value; and

- B) texts that trouble us today almost certainly troubled our ancestors, too.

It’s a relief to know, for example, how the ancient Rabbis read the verse about the rebellious child: They looked carefully at the language and decided that use of the singular expression, “voice” for two people means that these conditions apply only if a child disobeys two parents who speak identically, at once, and the parents are alike in appearance and stature; this, the Rabbis declared, was so unlikely that such a case never happened and never would. Instead, they said, the verse was put there for study purposes only.

So that is one commandment that no Jewish community observes. But there are others in this portion that many Jews do observe – and that fact can complicate study for Jews who don’t observe in the same way.

After more than a century of distancing itself from all ceremonial and ritual commandments, the Reform movement shifted gears with the 1999 Platform, saying: “We are committed to the ongoing study of the whole array of mitzvot and to the fulfillment of those that address us as individuals and as a community.” See below for a few words from the 18 85 and 1999 platforms and a link to the full texts (and/or p.3 of PDF); I think it’s worthwhile to review these things from time to time.

85 and 1999 platforms and a link to the full texts (and/or p.3 of PDF); I think it’s worthwhile to review these things from time to time.

As the 1999 platform suggests, even if we don’t observe particular commandments, studying them can remind us that our tradition is richer and deeper, and sometimes stranger, than a quick reading or online search might suggest. I say “strange” both in the sense of “not known before” and in the sense of “odd” or “out of place,” because Torah teachings from one Jewish culture can seem quite strange to Jews from another community. This is especially evident when we’re talking about commandments that are carefully observed by some Jews but practically unknown by others.

For Jews who don’t observe family purity laws or kashrut, for example, details of these laws might seem irrelevant, old-fashioned, or preachy. But many Jewish teachings, including most from previous centuries, assume knowledge and interest in these areas. So skipping over all such teaching means missing a lot. There’s a great deal to be learned in foreign Torah territory, and different sets of assumptions are not necessarily meant to be inhospitable. The key, I think, is to do some advance planning to make the most of the trip. And that’s what I hope we can do this morning, as we head into possibly unfamiliar landscape in search of new perspectives on Amalek, on repentance and making changes in the world.

- Left Field: insurancenewsnet.com

The first bit of background might seem out of left field for exploring Amalek,

Consider, however, that throws from deep in the outfield can have a big impact on the game.

Work and Shabbat

In Genesis 2:2, God ceases God’s melachah, creative work, and rests on the Sabbath. (Verses and more details below and/or page 3 of PDF.)

In Exodus 31, God is giving instructions for building the Tabernacle, and the People are told that melachah, creative work, is forbidden on the Sabbath in imitation of God’s rest.

Later Jewish tradition, beginning with the Talmud, lists 39 categories of melachah – like tying knots, bleaching, spinning, and carrying things –

based on the kind of work that was needed to construct the Tabernacle.

One of the prohibited kinds of melachah is “mocheik al m’nat lichtov” – erasing with the intention to write something new in that same place:

…Erasing merely to blot out what is written is a destructive act, and destructive acts are not forbidden on Shabbat by Torah law. Melachah is constructive activity, similar to God’s creative acts when forming the universe.

So what form of erasing is prohibited on the Sabbath? “Mocheik al m’nat lichtov” — erasing with the intention of writing again. One’s intention must be to clean the surface in order to write over the original letters. This type of erasing is a positive, constructive activity, and therefore is incompatible with the special rest of the Sabbath day.

— “True Erasing” from Rav Kook on parashat Ki Teitzei

(See also Language Note below; source #17 on PDF)

This is where that throw from left field reaches the infield, as Rav (Rabbi Abraham Isaac) Kook explains that this is the kind of erasing required to obliterate Amalek’s name.

This is where that throw from left field reaches the infield, as Rav (Rabbi Abraham Isaac) Kook explains that this is the kind of erasing required to obliterate Amalek’s name.

Remembering Amalek

So, now let’s take a few moments to remember Amalek, as we’re told to do

at the close of this week’s portion.

There are five biblical texts dealing with Amalek on the source sheet (sources 1-5 and below). Amalek appears a few more times in the Torah and later in the Tanach, but these are the most important ones for our story this morning.

We recall that Amalek is the grandson of Esau and great-great-grandson of Abraham and Sarah. Esau is the one who was tricked out of the first-born’s blessing by his twin brother, Jacob, who becomes Israel. That makes him our family, too, however thoroughly estranged.

In Exodus, Amalek launches an unprovoked attack on the Israelites in the wilderness, and God declares war with Amalek from generation to generation. In this week’s portion, we learn new information about that incident: that Amalek had attacked the weakest stragglers and that Amalek did not fear God.

Later, the Book of Samuel and the Book of Esther each reference more generations of Amalek and Israel as enemies – we are becoming more and more distant cousins, but still family. Rabbis Arthur Waskow and Phyllis Berman suggest that we view the two peoples as “connected to each other like conjoined twins. If I assault my twin, I am wounding myself….”

And that brings us to “My Brother Esau.” This song captures an important idea, shared by many Jewish teachers, about the relationship between Israel and Esau, and by extension, Amalek. The lines “the more my brother looks like me,” and “though he gave me all his cards,” in particular, touch on the thread of Jewish teaching that sees Esau and Amalek as other aspects of ourselves, like Jacob and Yisrael are sometimes understood as two aspects of one individual.

Obliterating Amalek

Returning to this week’s portion, we are told:

- to remember זָכוֹר

Remember what Amalek did to the Jewish people;

- to blot out the remembrance תִּמְחֶה

Wipe out the descendants of Amalek from under heaven

תִּמְחֶה אֶת-זֵכֶר עֲמָלֵק, מִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמָיִם; and

- to not forget לֹא, תִּשְׁכָּח

Not to forget Amalek’s atrocities/ambush on our journey from Egypt in the desert.

These are usually understood as three separate commandments, following Maimonides.

Over the centuries, Jews of many different belief systems have struggled with whether, and how, those commandments – especially the one to wipe out a whole people – still apply. See, for a really helpful and accessible summary, “Are Jews Still Commanded to Blot Out the Memory of Amalek?”

Professor Golinkin, like Nechama Leibowitz and others before him, focuses on the two new statements in this week’s portion: that Amalek did not fear God, and that he attacked the vulnerable. (See below for excerpt and link to the full article; p.2, PDF.)

Many teachers see the joining of these in the text as evidence that failing to care for the weak is a failure to fear God, and vice versa.

Finally, now, that throw from left field makes it all the way to the plate.

Finally, now, that throw from left field makes it all the way to the plate.

In Exodus 17, there are two odd spellings that caught the attention of commentators: “Throne” is spelled with two letters instead of the usual three – that is, keis, instead of kisei – and God’s name is spelled with only two letters – yud-hey, instead of the four-letter name. (p.1 PDF or below)

Completing God’s Name

In many different readings, Amalek represents attempts to erase God’s name, either by unethical behavior that harms the image of God in others or by trying to remove “Yisrael,” a nation which contains God’s name. The latter is Rav Kook’s view:

We are charged to replace Amalek with the holy letters of God’s complete Name. We must restore God’s complete throne – i.e., God’s Presence in the world – through the special holiness of the Jewish people, who transmit God’s message to the world.

Rav Kook says we can see from these shortened words that all is not right with God’s name in the world after the encounter with Amalek. And this means that simply erasing Amalek’s name won’t put things right.

Returning to the concept of melachah, some erasing is just destructive.

And, even though it might seem contrary to the spirit of Shabbat,

destruction is not actually among the 39 categories of prohibited action.

Only creative acts.

Similarly, Rav Kook explains, the mitzvah is not simply to obliterate Amalek so that there will no longer be any more Amalekites in the world. That would be a purely destructive act.

The destruction of Amalek must have a productive goal. We must obliterate Amalek, with the intention of ‘transforming the world into a kingdom of the Almighty.’

Rav Kook, in The Moral Principles, tells us that Amalek’s name is to be erased only from under heaven. Meaning that somewhere, however twisted, there was a good intention in Amalek that should be recognized and not destroyed. This effort requires a “lofty state of purity,” which Rav Kook doesn’t think too common. But the aspiration is still instructive, especially, for Elul. (See source #9 below; p.1, PDF)

Elul Thoughts

So much of the advice around teshuva focuses on one-way apologies and single-handed attempts to change our behavior. One-way changes are important for our souls and, no doubt, to those whom we’ve wronged. But we live in relationships and community. And Rav Kook’s two teachings on Amalek together suggest that it’s not enough to beat down evil urges or repair individual wrongs. What we need to do is to approach places where we, as individuals or groups, have allowed the non-God-fearer’s name to appear and erase it with the intention of writing something better. Destruction – even of an evil, in ourselves, or in a relationship, with a brother or an enemy – is only half the task. The real God-imitating work is in destroying in order to rebuild something better in ourselves, in our relationships and in the wider world.

Now, let’s return for a moment to the wider concept of melachah and Shabbat. Like most of us here today, I observe Shabbat in a way that does not involve understanding details of the 39 different categories of melachah associated with building the Tabernacle, and avoiding them on Shabbat. So, I don’t usually worry about whether a particular kind of writing or erasing is allowed on Shabbat. And I know I’m not alone in this.

Looking at Rav Kook’s very specific teaching, however, shifted my understanding of Shabbat. For a long time, I’ve endeavored to avoid computer and internet, work-related calls, and money-related talk on Shabbat. This helps me separate the Sabbath from the six days and also to explain what I do and don’t do on Saturdays to other people. But I don’t avoid kindling, travel beyond my neighborhood, or many other forms of melachah, including many kinds of creation.

And I realized just a few days ago that I had really missed the main point here. There’s powerful value in making Shabbat with my husband, in our own way. But I am now paying more attention to the concept of ceasing to create because even God took a day off from essential, productive, maybe enjoyable, activities –rather than because it suits me in some ways to take a break.

…That brings me to this short story by Sharon Strassfeld, and to this note: What-, who-, or however we envision God — or even if we don’t really think of God at all — it’s important to consider, especially as we enter the high holidays season, that we’re not God. (Story also in plain text below for those who don’t do graphics; p.4, PDF in graphic form.)

Erasing and Learning

Finally, consider this verse from Pirkei Avot, mentioning “machok,” blotting:

לִישָׁע בֶּן אֲבוּיָה אוֹמֵר, הַלּוֹמֵד יֶלֶד לְמַה הוּא דוֹמֶה, לִדְיוֹ כְתוּבָה עַל נְיָר חָדָשׁ.

וְהַלּוֹמֵד זָקֵן לְמַה הוּא דוֹמֶה, לִדְיוֹ כְתוּבָה עַל נְיָר מָחוּק

Elisha ben Abuya said: When you learn as a child, what is it like? Like ink written on clean paper.

When you learn in old age, what is it like? Like ink written on blotted paper [a sheet from which the original writing has been erased]

– Avot 4:25 (or 4:20)

Until a few days ago I thought this was the saddest Mishnah I’d ever seen. This is the only place where Elisha Ben Abuya‘s name appears. Everywhere else in the Talmud, he’s referred to as Acher, “the Other,” for complicated reasons, relating to this week’s portion, that led to his becoming a heretic and a symbol of rabbinic failure.

I kept thinking about Elisha Ben Abuya’s struggles with community and faith. And the idea that he saw adult learning as such a difficult, messy process – like trying to write on parchment that was already used and scraped off – broke my heart.

But then, in studying this portion and Rav Kook’s teachings, I had a new idea:

Maybe all he’s really saying is that anyone who is trying to learn something and is not a small child – whether we’re 12 or 13 or 55 or 85 – is probably erasing some previous, maybe erroneous or partial, understanding of the world. And that is not sad at all. In fact, as I just learned: writing, as well as erasing with the intention to write something new, are both understood as creative work that imitates God. This is what I think we have to keep in mind as we move through Elul and into the Days of Awe.

Our job is not to aim for a clean slate – apologies for mixing metaphors with all that parchment scraping – but to work with what is already written, to make corrections where need be, and to keep trying to write a better story for this new year and beyond.

I hope this made some sense.

Please feel free to contact me if anything was unclear.

With best wishes for a productive Elul and high holiday season.

NOTE: The text above is a dvar torah given at Temple Micah (DC) on August 25. Micah live streams and archives services, so video can be found at Temple Micah (dvar torah about about 50 minutes after the service began). As mentioned above, the four-page source sheet is meant to accompany this drash but also stand on its own. Ki Teitzei source sheet (PDF).

BACKGROUND SOURCES

Amalek in Biblical Text

[1] Amalek is great-great grandson of Abraham and Sarah:

And these are the generations of Esau the father of a the Edomites in the mountain-land of Seir….And Timna was concubine to Eliphaz Esau’s son; and she bore to Eliphaz Amalek….

–Gen 36:9-12

[2] In the wilderness, Amalek attacks Israel, who prevails; God declares war against Amalek, “from generation to generation”:

Then came Amalek, and fought with Israel in Rephidim….And Joshua discomfited Amalek and his people with the edge of the sword. And the LORD said unto Moses: ‘Write this for a memorial in the book, and rehearse it in the ears of Joshua: for I will utterly blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven.’

כִּי-מָחֹה אֶמְחֶה

אֶת-זֵכֶר עֲמָלֵק, מִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמָיִם

And Moses built an altar, and called the name of it Adonai-nissi. And he said: ‘The hand upon the throne of the LORD: the LORD will have war with Amalek from generation to generation.’

וַיֹּאמֶר, כִּי-יָד

עַל-כֵּס יָהּ, [throne of the LORD]

מִלְחָמָה לַיהוָה, בַּעֲמָלֵק–מִדֹּר, דֹּר –Exodus 17:8, 13-16

See also Language Note below.

[3] Two details about the Exodus story appear in this week’s portion:

…how he met you by the way, and smote the hindmost of you, all that were enfeebled in your rear, when you were faint and weary; and he feared not God…–Deut 25:18

[4] Enmity between Amalek and Israel persists:

Thus saith the LORD of hosts: I remember that which Amalek did to Israel, how he set himself against him in the way, when he came up out of Egypt. Now go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have, and spare them not…

And Saul smote the Amalekites…. And he took Agag the king of the Amalekites alive, and utterly destroyed all the people with the edge of the sword. –1 Sam 2-3, 7-8

[5] Agag’s survival, contrary to instruction, led to the Purim story:

After these things did king Ahasuerus promote Haman the son of Hammedatha the Agagite, and advanced him, and set his seat above all the princes that were with him. –Esther 3:1

BACK

[8] THRONE and NAME

“Why is the word for ‘throne’ shortened, and even God’s Name is abbreviated? God swore that His Name and His Throne are not complete until Amalek’s name will be totally obliterated.” – from Tanchuma, Ki Teitzei 11; Rashi

Then came Amalek, and fought with Israel in Rephidim….And Joshua discomfited Amalek and his people with the edge of the sword. And the LORD said unto Moses: ‘Write this for a memorial in the book, and rehearse it in the ears of Joshua: for I will utterly blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven.’

כִּי-מָחֹה אֶמְחֶה אֶת-זֵכֶר עֲמָלֵק, מִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמָיִם.

And Moses built an altar, and called the name of it Adonai-nissi. And he said: ‘The hand upon the throne of the LORD: the LORD will have war with Amalek from generation to generation.’

וַיֹּאמֶר, כִּי-יָד

עַל-כֵּס יָהּ, [throne of the LORD]

מִלְחָמָה לַיהוָה, בַּעֲמָלֵק–מִדֹּר, דֹּר –Exodus 17:8, 13-16

BACK

[9] from The Moral Principles

The degree of love in the soul of the righteous embraces all creatures, it excludes nothing, and no people or tongue. Even the wicked Amalek’s name is to be erased by biblical injunction only “from under the heavens” (Ex 17:14). But through “cleansing” he may be raised to the source of the good,* which is above the heavens, and is then included in the higher love. But one needs great strength and a lofty state of purity for this exalted kind of unification.

– Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935), The Moral Principles.

Ben Zion Bokser, trans. Paulist Press, 1978, p.137

*Kook believed that an evil deed is an impulse that at its highest source of origin was good but became distorted and went astray. The first Ashkenazi chief rabbi in pre-state Israel, he published on ethics and mystical teachings.

BACK

[11]

Amalek and Jews Today

Over the centuries, Jews have argued about whether, and how, those commandments still apply. Many interpreters have identified Amalek with one real life enemy or another, historical or contemporary, from ancient Rome to the Soviets or Nazis; Jews have called other Jews “Amalek,” and some Christians have seen themselves as “Israel” and their enemies, including Jews, as “Amalek.” Others have said that Amalek no longer exists or taken a metaphorical view. – Summarized from Golinkin (citation below).

The 20th Century teacher Nechama Leibowitz explores Deut 25:18 in the context of Torah passages mentioning fear of God, or lack thereof. She notes that each passage focuses on caring for the most vulnerable among us, or failing to do that. Therefore, she writes:

“Amalek” against whom the Almighty declared eternal war is not any more an ethnic or racial concept but is the archetype of the wanton aggressor who smites the weak and defenseless in every generation.

Golinkin quotes Leibowitz and concludes:

In our day, this is perhaps the most important message of the Amalek story — not hatred of Amalek but aversion to their actions. In the State of Israel, there are many strangers and stragglers — new immigrants, foreign workers, as well as innocent Arabs and Palestinians. Some Jews learn from the story of Amalek that we should hate certain groups. We must emphasize the opposite message. We must protect “the stragglers” so that we may say of the State of Israel: “surely there is fear of God in this place”.

– “Are Jews Still Commanded to Blot Out the Memory of Amalek?”

Prof. David Golinkin is president of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem; highly recommend this thorough, readable article.

BACK

[12]

“My Brother Esau”

Words by John Perry Barlow; music by Bob Weir.

First performed by Grateful Dead in 1983:

Esau holds a blessing;

Brother Esau bears a curse.

I would say that the blame is mine

But I suspect it’s something worse.

The more my brother looks like me,

The less I understand

The silent war that bloodied both our hands.

Sometimes at night, I think I understand.

…It’s brother to brother and it’s man to man

And it’s face to face and it’s hand to hand…

We shadowdance the silent war within.

These words are alternative wording, maybe Bob Weir forgetting lyrics as written or creating new ones, March 1983:

Esau tried to move away

A marvelous disguise

Where every street is easy

and, there’s nothing to deny

Though he gave me all his cards

I could not play his hand

Made a choice

Soon became a stand

Full lyrics and annotations here.

BACK

[13]

Work and Shabbat

Work/Service/Worship = Avodah. (Creative) Work= Melachah:

וַיְכַל אֱלֹהִים בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי, מְלַאכְתּוֹ אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה; וַיִּשְׁבֹּת בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי, מִכָּל-מְלַאכְתּוֹ אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה

And on the seventh day God finished His work [melachto] which He had made; and He rested on the seventh day from all His work which He had made. – Gen 2:2

וּשְׁמַרְתֶּם, אֶת-הַשַּׁבָּת, כִּי קֹדֶשׁ הִוא, לָכֶם; מְחַלְלֶיהָ, מוֹת יוּמָת–כִּי כָּל-הָעֹשֶׂה בָהּ מְלָאכָה, וְנִכְרְתָה הַנֶּפֶשׁ הַהִוא מִקֶּרֶב עַמֶּיהָ

You shall keep the sabbath, for it is holy unto you; every one that profanes it shall surely be put to death; for whosoever does any work [melachah] therein, that soul shall be cut off from among his people.

שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים, יֵעָשֶׂה מְלָאכָה, וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי שַׁבַּת שַׁבָּתוֹן קֹדֶשׁ, לַיהוָה; כָּל-הָעֹשֶׂה מְלָאכָה בְּיוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת, מוֹת יוּמָת

Six days shall work [melachah] be done; but on the seventh day is a sabbath of solemn rest, holy to the LORD; whosoever does any work [melachah] in the sabbath day, he shall surely be put to death.

וְשָׁמְרוּ בְנֵי-יִשְׂרָאֵל, אֶת-הַשַּׁבָּת, לַעֲשׂוֹת אֶת-הַשַּׁבָּת לְדֹרֹתָם, בְּרִית עוֹלָם

Wherefore the children of Israel shall keep the sabbath, to observe the sabbath throughout their generations, for a perpetual covenant.

בֵּינִי, וּבֵין בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל–אוֹת הִוא, לְעֹלָם: כִּי-שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים, עָשָׂה יְהוָה אֶת-הַשָּׁמַיִם וְאֶת-הָאָרֶץ,

וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי, שָׁבַת וַיִּנָּפַשׁ

It is a sign between Me and the children of Israel for ever; for in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day He ceased from work and rested.’ – Ex 31:14-17

Later Jewish tradition, beginning with the Talmud, lists “forty minus one” categories of melachah – like tying knots, bleaching, spinning, and carrying things – related to building the Tabernacle, as prohibited on Shabbat. (There’s a 40th category, which is Creation with a capital “C,” but people cannot imitate God in that way, so that’s not included among the prohibitions.)

Very nice resource on this can be found at Ask Moses.

BACK

[14]

Reform Movement and Commandments

1885 Pittsburgh Platform

…We recognize in the Mosaic legislation a system of training the Jewish people for its mission during its national life in Palestine, and today we accept as binding only the moral laws, and maintain only such ceremonies as elevate and sanctify our lives, but reject all such as are not adapted to the views and habits of modern civilization….

1999 Platform

…We are committed to the ongoing study of the whole array of mitzvot and to the fulfillment of those that address us as individuals and as a community. Some of these mitzvot, sacred obligations, have long been observed by Reform Jews; others, both ancient and modem, demand renewed attention as the result of the unique context of our own times….

…We bring Torah into the world when we seek to sanctify the times and places of our lives through regular home and congregational observance. Shabbat calls us to bring the highest moral values to our daily labor and to culminate the workweek with kedushah, holiness, menuchah, rest and oneg, joy….

Full text at Reform Platforms at CCAR

BACK

[16] Strassfeld’s short story:

When I was a teenager, I began reading philosophical works. I concluded that God did not rule the world that in fact we and God were partners. One Yom Kippur in consonance with my new thinking I decided not to “fall korim” (prostrate myself) for the aleinu prayer. My zaydee, who had eagle eyes even for the upstairs women’s balcony, asked me to take a walk with him during the break in services. He wondered, he told me, why I hadn’t fallen korim. I explained that it was a “neue velt” (literally, a “new world”) now and the old-fashioned ideas of God ruling everything and people scurrying around to do God’s command no longer made sense. Zaydee listened and then asked thoughtfully, “Sherreleh, tell me more about this neue velt. I did, telling him all about the things I had been reading and thinking. When I finished, my grandfather said to me, “This new world you speak about I understand. But there is one thing I don’t understand. In this new world, if you don’t bow before God, before whom will you bow?”

– Sharon Strassfeld. Everything I Know: Basic Life Rules from a Jewish Mother. NY: Scribner, 1998

BACK

LANGUAGE NOTES

כִּי-מָחֹה אֶמְחֶה

אֶת-זֵכֶר עֲמָלֵק, מִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמָיִם (Ex 17:8)

[6] נִמְחָה – to be obliterated, forgotten, destroyed, or eliminated

מָחָה – to erase [or wipe, as dishes], to obliterate, to blot out the memory of ; (literary) to wipe away, to dry (tears, sweat)

[7] OED: “Erase” is a newer (17th Century) than “blot” (15th Century). “Erase” may have come from older word “arace,” to uproot. A “blot” in backgammon is a lone, vulnerable piece. BACK to Exodus 17

[17]“Mocheik al m’nat lichtov”

to erase, to delete ; to blot out – מָחַק

eraser, rubber – מַחַק

BACK to Rav Kook on erasing — BACK to Elisha Ben Abuya

Citations:

Waskow, Rabbi Arthur O. and Rabbi Phyllis O. Berman. Freedom Journeys: The Tale of Exodus and Wilderness across Millennia. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights, 2011. p.155 BACK

More on Acher [Aher, “The Other”], Elisha Ben Abuya:

“A Path to Follow” Ki Teitzei, note on how a verse this portion led is said to have led to Acher’s heresy.

Different stories about Elisha Ben Abuya from the midrash. Much more in the Fabrangen blog on related topics.

A warning about dualism as the four enter Pardes

See also “Daughter of Acher”

BACK

85 and 1999

85 and 1999

This is where that throw from left field reaches the infield, as Rav (Rabbi Abraham Isaac) Kook explains that this is the kind of erasing required to obliterate Amalek’s name.

This is where that throw from left field reaches the infield, as Rav (Rabbi Abraham Isaac) Kook explains that this is the kind of erasing required to obliterate Amalek’s name. Finally, now, that throw from left field makes it all the way to the plate.

Finally, now, that throw from left field makes it all the way to the plate.