Chapter 34 of Genesis begins with a woman going to visit neighbors. It is one of very few instances in Genesis — maybe the only one? — of an apparently friendly, non-transactional interaction with folks of the surrounding culture. And one of the few instances in Genesis in which a woman has any agency. This episode is part of the Torah portion Vayishlach (Gen 32:4-36:43). The commentary is inspired by Joni Mitchell and “The Last Waltz,” concert and film, as well as Dinah’s story

CONTENT WARNING: What follows is mostly about music and crossing boundaries of various kinds in contemporary society. But Dinah’s story cannot be separated from disturbing underlying topics, including misogyny, racism, and sexual violence.

UPDATED afternoon of 12/5/25: mostly edits to correct typos and awkward grammar; some new phrasing in the Joni Mitchell, Now and Then section and a few new paragraphs at the end. Apologies for any confusion… still thinking.

Existing in Public

In Genesis 34:1, Dinah, “went out [teitzei] to see the women of the land.” The single verse relating this scene describes Dinah as “daughter of Leah, whom she had borne to Jacob.” (More below on Dinah and her going out, and a little about her parents.)

This “going out” is the only verb attributed to Dinah and the only time that other women are mentioned in Chapter 34. One verb. One verse of agency. And no voice.

The text itself does not criticize Dinah for going out or denigrate the women she went to visit. But the consequences of this one woman exercising agency and existing in public for the space of one verse are dramatic and dire. This reverberates in so many aspects of US society today, and in history, where simply existing in public is understood by some as provocation:

- walking or driving while Black;

- being queer in public;

- living with brown skin or other signs of “possible immigrant” status;

- being “too Jewish” or Jewish in the “wrong place” or the “wrong” kind of Jewish;

- playing sports without identifying strongly with one gender;

- existing as a transgender person;

- expressing support for Palestine;

- appearing in any way that resists authoritarianism;

- what we used to call “doing your own thing” among folks strongly committed to some other way of being.

At various points in US history, whatever white people performed on stage or dance floor was eventually accepted as mainstream, while “Black music” was/is continually viewed as dangerous and in need of policing by white nationalism:

Jazz. Here in Germany it become something worse than a virus. We was all of us damn fleas, us Negroes and Jews and low-life hoodlums, set on playing that vulgar racket, seducing sweet blond kids into corruption and sex. It wasn’t music, it wasn’t a fad. It was a plague sent out by the dread black hordes, engineered by the Jews. Us Negroes, see, we was only half to blame – we just can’t help it. Savages just got a natural feel for filthy rhythms, no self-control to speak of. But the Jews, brother, now they cooked up this jungle music on purpose. All part of their master plan to weaken Aryan youth, corrupt its janes, dilute its bloodlines.

…we was officially degenerate.

…And poor damn Jews, clubbed to a pulp in the streets, their shopfronts smashed up, their axes ripped from their hands. Hell. When that old ivory-tickler Volker Schramm denounced his manager Martin Miller as a false Aryan, we know Berlin wasn’t Berlin no more. It had been a damn savage decade.

–Sid, Black musician narrator, in Esi Edyugan’s Half-Blood Blues: A Novel Picador, 2011 p.78-79

Further discussion of Edyugan’s novel, racial and music history, and how Germany in the 1930s relates to US history and my own story; plus whole series from 2016 on related topics.

In a somewhat similar vein, women’s and queer people’s existence continues to be viewed as dangerous in many quarters and in need of policing by cishet men and white nationalists.

Joni Mitchell, Then and Now

With US Thanksgiving, I am often reminded of “The Last Waltz” as a film and soundtrack, both of which have been important parts of my world for decades. And, most years, I re-discover how angry I still am at the film’s treatment of Joni Mitchell as an artist and human being. It is only in the last 10 or 15 years, that I’ve learned just how much of the film’s presentation was NOT what the original concert offered; instead, Martin Scorsese chose, and popular attitudes to women permitted, deliberate manipulation of concert footage in ways that denigrate Mitchell and every woman, in- and beyond the arts.

Details here —

I wrote the above piece a few years ago, in a week associated with a different part of the Torah, and on the heels of Mitchell’s surprise appearance at Newport that year (2022). I recently updated some of this post’s language for clarity and to add a few new links.

This year (2025), I had the opportunity to attend a tribute to “The Last Waltz” at a music venue just outside of Chicago. In many ways it was a great concert and a terrific experience. However, unless I misunderstood his meandering words, the musician-emcee called Joni Mitchell a tramp while introducing “Coyote.” I think he believed he was being funny, and maybe he meant to illustrate double-standards that existed then and still operate. But I was mostly struck with how hard the world can still — after 50 years! — push back when many people are just trying to exist, live their life, and engage their art.

Defending and Celebrating “Going Out”

We only get his one verse, in the midst of such a wildly disturbing story, that tells of Dinah’s going out. And we don’t learn much, if anything, about the rest of the family engaging with local culture or making friends. Is the Torah trying to tell us how dangerous it is to be going out into the surrounding culture? If so, when did that emphasis come into the telling? And what might we learn by focusing on the importance of going out and what we miss if we fear it or are attacked for doing so?

UPDATE 12/5 afternoon, four paragraphs and image added here:

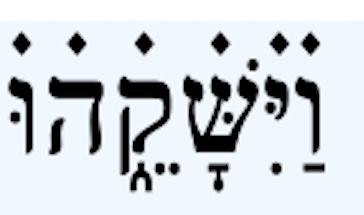

When Esau and Jacob meet, after decades apart, the Torah text includes dots above the word va-yishakeihu [and he kissed him] in Genesis 33:4: “Esau ran to meet him; he embraced him, flung himself upon his neck, and kissed him. And they wept.”

For centuries, Jewish teaching has used these dots to suggest that the text be read in opposition to its straightforward meaning: instead of kissing Jacob, Esau was insincere in his greeting or perhaps trying to bite or otherwise do Jacob harm. (Find the text and commentary at Sefaria.)

As part of the deliberate demonization of Esau, unsupported by the Torah itself, this dotted reading is one of my least favorite aspects of Torah commentary. It seems very like Scorsese’s use of interview footage to completely alter how viewers are introduced to Joni Mitchell. And all too resonant with dangerous propaganda through the ages. However, the dots also offer a powerful example of how Jewish tradition has always found a way to read with some skepticism, even change the text where warranted.

Jacob went out; Leah went out; Dinah went out. Maybe we, too, can go out into Torah readings that put us in better touch with our families, our neighbors, and the world at large. Where Torah has been weaponized, we can learn to acknowledge harm and promote better readings. And where our culture, in- and outside of Judaism, has tricked us into thinking the worst of others, maybe we can work to undo the propaganda.

NOTES

Dinah Went Out

Prior to Genesis 34, Dinah is previously mentioned only at her birth and naming (Gen 30:21). Dinah, daughter of Leah and Jacob, has no voice of her own in the text, and we never hear from Leah or any other women of Jacob’s household or the town regarding her fate. Instead, men act on and about Dinah: She is an object — of lust or love, depending on translation/interpretation — for the prince, who is seen lurking here in R. Crumb’s illustration —

Then Dinah is the object of various decisions and actions by the prince, his father, other men of the local town, and her own father and brothers. Over the centuries, Dinah’s “going out” has been variously interpreted as

- involving herself — for better or worse, depending on the commentary’s perspectives and biases — in the existing culture;

- spying on the women of the land;

- showing off her wealth;

- seeking women’s companionship in a non-romantic sense;

- checking out the women as potential romantic partners;

- seeking inappropriate attention, with some teachers insisting that a woman seeking any attention at all is inappropriate (and potentially dangerous);

- acting forward, as Leah’s going out to meet Jacob (Gen 30:16) is often characterized, with the implication that women must be restrained;

- simply moving through the world, which the text itself does not condemn, perhaps akin to Jacob’s going out to find his way (Gen 28:10).

**Alt Text: graphic frame for Gen 34:1-2 shows Dinah visiting congenially with a few women in what appears to be a public square, while the prince looks on from behind a nearby building column. R. Crumb’s Illustrated Book of Genesis uses Robert Alter’s 1996 translation: “And Dinah, Leah’s daughter, whom she had borne to Jacob, went out to see some of the daughters of the land. And Shechem, the son of Hamor the Hivite, prince of the Land, saw her…”

Commentary on Dinah’s Story

Rashi (11th Century CE France) notices that Leah previously “went out” (Gen 30:16): “like mother, like daughter.” Rashi adds a note about the need for men to subdue wives from public activity.

Ibn Ezra (12th Century CE Spain) says: AND DINAH WENT OUT. Of her own accord — as in: She did not ask her parents’ permission.

Ramban (13th Century CE Spain) says “bat Leah” is links Dinah to Simeon and Levi, who are also children of Leah and so are moved to avenge her [due to perceived defilement]

The Torah: A Women’s Commentary (CCAR Press, 2008) notes that Jephthah’s daughter “went out to meet him,” using the same yud-tzadei-aleph verb (Judges 11:34) with horrible consequences. That volume has more on Dinah. See also “The Debasement of Dinah” and “A Story that Biblical Authors Keep Revising” Dinah and Schechem” at TheTorah.com.

Women’s Archive on Dinah in historical midrash.

Some relatively contemporary notes on Dinah. While some people treat Anita Diamant’s novel, The Red Tent (St. Martin’s Press, 1997), as midrash, the author herself says it is historical fiction.

An exploration of Dinah as transgender.

Note also that Leah goes on to live with Jacob on “the land,” while Rachel seems strongly linked to her family’s original home, “back there,” and dies on the road giving birth to the only child born in “the land.” (More on these aspects of the story found in this older post.)

Notes on “subdue it/her”

Rashi and Genesis Rabbah to Gen 34:1

Rashi cites Genesis Rabbah (4th Century, Talmudic Israel), which uses Gen 34:1 as proof text for why men should subdue their wives: Gen 1:28 tells humans to “…fill the earth and subdue it/her [mil’u et ha-‘aretz v’khivshuha…].” The Hebrew verb construction v’khivshuha uses the feminine direct object ha [it/her] to match the feminine noun ‘aretz. Commentary plays on that grammatical feature to read “subdue her [the woman],” rather than the more common “subdue it [the earth],” bringing Gen 34:1-3 as explanation: “the man subdues his wife so she should not go out in public, as any woman who goes out in public will ultimately falter.” Implication is that Dinah “faltered” by allowing herself to come in contact with Shekhem (Gen 34:2); depending on reading of va-y’aneiha, this means either that Dinah allowed herself to be “humbled” by consensual association with Shekhem or that she made herself vulnerable to physical attack or social violation by “going out,” i.e, simply being a woman in public space.

-#-