The end of the handout is the result of the earlier parts of my studies, a brief exploration into Mishkan T’filah and earlier drafts of the siddur, mostly focusing on one pair of pages where we find: “Six Torah episodes are to be remembered each day, to refine our direction.”

The “Six Torah episodes” section can be found on pages 43 and 205 in the actual Mishkan T’filah, on page 12 in the handout, shared here.

In similar passages (more on this later) in other prayer books, “What God did to Miriam” is included here. I turned to older drafts of Mishkan T’filah, hoping they might clue me into why Miriam is not on this page.

Endnote Deadend

An endnote in the published siddur says the Six Torah episodes were “adapted from a Sephardic siddur.” But it doesn’t specify which or say what was adapted. I could find no example anywhere, Ashkenazi or Sephardic, in another siddur which changes the verses so as to omit Miriam, as Mishkan T’filah does. Every other example over the last 1000 years seems to focus on the same six incidents, all of which include a Torah verse demanding that we “remember” and/or “not forget.” Only Mishkan T’filah uses a different list. Only Mishkan T’filah leaves out specific Torah verses. And only Mishkan T’filah adds in Korach — about whom we have no memory admonition in the Torah.

These seem significant differences, and I thought it a little odd that so much changed over the course of the drafts, while this passage remained static through five years or more of edits. (See the handout for some notes on changes that did occur over the drafts.) No one I asked — including some Temple Micah clergy, current and past, and other people I thought might know — had an explanation. Rabbi Gerry Serotta, who served as interim rabbi some years ago, sent a query on my behalf to the siddur’s chief editor, Rabbi Elyse Frishman, and to Rabbi David Ellenson. If we hear back, I’ll let you know.

Improvement by Removal?

Meanwhile, Rabbi Gerry and I guessed that removing Miriam had been an attempt to respond to feminist criticism about how Miriam is usually remembered: 1) focusing on her case of tzaraat, a skin condition, rather than on anything she actually did or who she was; 2) remembering “What God did to Miriam” in a way that accuses her of lashon hara [evil speech], although that is unclear in the text; and 3) blames Miriam alone, while the text clearly states that both Aaron and Miriam spoke against Moses (Numbers 12:1ff).

If it’s true that the change was made due to feminist sensibilities, it seems ironic — and oddly instructive — that, as a result, Miriam is… just gone.

Acquiring Memory

In my travels through older prayerbook drafts, I was intrigued by the adage, attributed to David Ellenson: “Acquire the memory of what it means to be a Jew.”

This prompted me to wonder:

- What did the siddur editors want us to remember with this set of episodes?

- What does it mean that Miriam is not on the page?

- What would it mean if she were there?

- What does it mean that Mishkan T’filah made this change without explanation?

- Would the passage land differently, had an explanation been included?

From there I followed many other branches of wondering, more generally, about how memory, and Jewish identity, are formed by our practice and our prayerbooks. That brings me to older material I found relating to the Six Remembrances.

On page three of the handout is a Talmudic source arguing why the verb “remember” should be understood to mean “repeat it with your mouth.” The link between speech and remembering is an old one in Jewish thought. The passage from Sifra discusses four of the verses in the Six or Ten Remembrances.

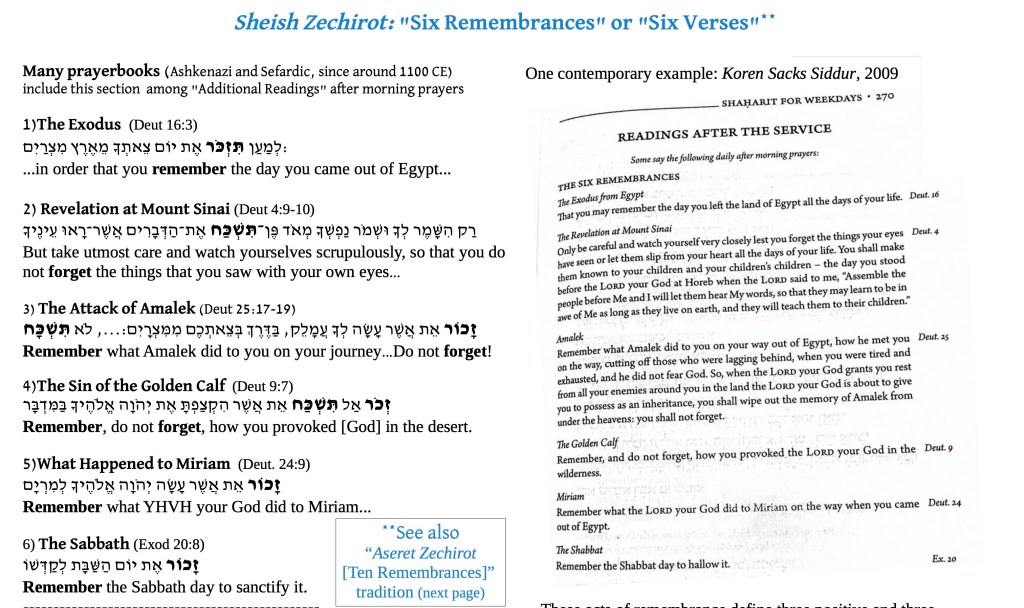

In addition to these four, the Exodus and the Revelation at Mount Sinai are included. Here, page 6 of handout, is a typical example of how the Six Remembrances appear in contemporary prayerbooks —

Intentions and Remembering

In addition to Mishkan T’filah’s “to refine our direction,” other intentions introduce these remembrances: from a simple “some say,” to “for the sake of unification of the divine name…” and “those who recite these are assured a place in the world to come.” (See page 2 of the handout for these various intentions and page 6 for details of how the Six and Remembrances and the “Six Torah episodes” differ.)

The Sifra passage also includes an expression that really caught my attention — the idea of “heart-forgetfulness,” apparently something that can be fixed with thought, while speech is required in other cases…..

This might be a good thing to keep in mind during Elul, thinking about what can be repaired by thought and memory and what requires speaking aloud.

Back to Miriam

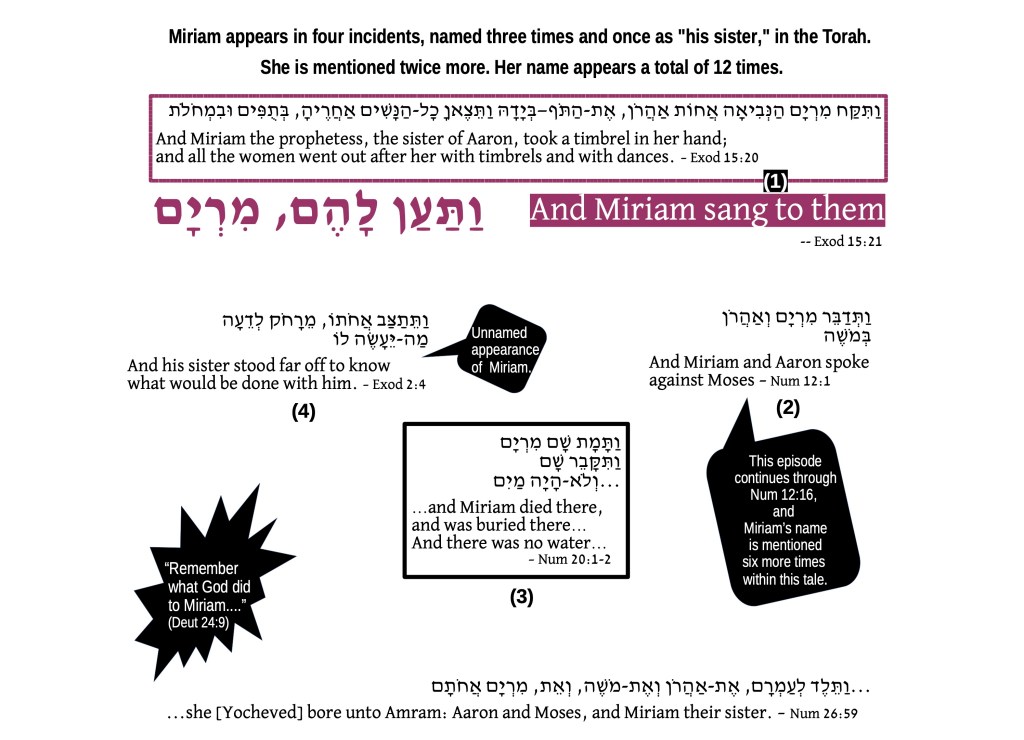

Now, back to Miriam, who is not on the Mishkan T’filah pages but IS in this week’s Torah portion (now last week’s, Ki Teitzei, Deut. 21:10 – 25:19 — pages 7 and 8 of the handout). Deuteronomy 24:9 is one of only 12 times her name appears in the Torah.

Rabbinic imagination saw Miriam’s Well in the white space between her death and the lack of water in the next verse. And many other stories and lessons surround Miriam. But she appears in four incidents in the Torah — named three times and “his sister” in another — and is mentioned twice more. That’s it. That’s all she wrote about Miriam.

There is a lot of commentary about the two verses in this week’s portion– the one telling the listener to heed the priests in matters of tzaraat (Deut 24:8) and the following one telling us to remember what God did to Miriam.

What God did to Miriam is related in Numbers 12. The demand that we remember what God did to Miriam is usually understood as a warning to guard the tongue, due to links in commentary between tzaraat and sins of the tongue. But it’s crucial to note that there is no direct link — either in this week’s portion or in Numbers 12 or elsewhere in Torah text — between Miriam and evil speech.

What and How We Remember

The story in Numbers 12 is full of obscure imagery, and Miriam’s tzaraat is the same condition Moses experienced at the Burning Bush, where it was part of his recognition as a prophet, and not understood as punishment at all. Early Jewish teachers chose to make Miriam an object lesson rather than following another set of interpretations with a different set of lessons.

None of the other Six or Ten Remembrances involve an individual, so — regardless of initial intention — Jewish thought and law were greatly influenced by the linkage that developed between Miriam, and women in general, and evil speech.

- But, is that a good reason to remove the text from recitation?

- Does that facilitate forgetting of a helpful kind?

- What is gained and what is lost in removing a passage with difficult associations?

- Might it be better to keep it in and work to understand and re-interpret?

Theologian Judith Plaskow discusses this in a piece on this week’s portion, “Tzaraat and Memory.” I highly recommend reading the whole thing — either in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, in print, or on My Jewish Learning.

Writing in 2008, Plaskow raises the issue of how progress can actually be a challenge to memory and to further progress. I’ll add that her conclusion can also apply to the appearance of progress, as when a problematic text is removed from regular recitation or consideration, or when we make changes that don’t always benefit the most harmed or vulnerable.

She writes, referencing the other important “memory” verses in this week’s portion:

We blot out the memory of Amalek when we create Jewish communities in which the perpetual exclusion of some group of people — or the denial of women’s rights — are so contrary to current values as to be almost incredible. Yet, if we are to safeguard our achievements, we can also never forget to remember the history of inequality and the decisions and struggles that have made more equitable communities possible.

What We Remember, What We Fix

I’ve been watching a series of mysteries focusing on women in the mid-1960s. (For fellow mystery fans: Ms. Fisher’s Modern Murder Mysteries, set in 1964-65 Melbourne, Australia, a delightful set of sequels to Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, set in the same area in the late 1920s.) And I’ve noticed that I am remembering, quite viscerally, how it FELT, as a girl and young woman, to have limited rights, opportunities, and expectations. And also of how dangerous it could be back then, in physical, legal, and psychic ways, for women and also for queer people and for many others….And I’m on the young side for these experiences; others have longer histories with inequality.

This exploration also reminded me of, on the one hand, how grateful I was to have to explain such things to our children as they were growing up. So many conversations that centered around: Queer people were forbidden from expressing their identity or acting on their sexuality, let alone getting married?! Women weren’t allowed to what?! US law defined whiteness as property and prevented Black people from what?!

On the other hand, I remember the desire to let them go on asking questions like “Do you have to be a mommy to lead services?” without ever realizing how impossible that question would have been in my youth and how painful it was for all of us who didn’t see ourselves reflected in leadership roles…or at all.

There is a strong tension between wanting to build a world with more equity and inclusivity, on the one hand, and the responsibility to never forget that we are sitting in a place built by damage; with many wounds still present, often unhealed, and so much work still to do. Continuing to REMEMBER, and recite, difficult passages can cause harm. But failing to remember carries it’s own risk.

The same applies in many ways to teshuva: When might it be appropriate to forget or not mention old harm, and when must we work to remember and confront? In other words, maybe, when are we dealing with heart-forgetfulness and when with something that requires us to use our mouths?

As I tried to figure out what happened with Miriam and the Six Torah episodes, I kept remembering these lines, from a song about memory and loss —

If you hear that same sweet song again,

will you know why?

— “Bird Song,” by Robert Hunter (1941-2019) & Jerry Garcia, z”l (1942-1995)

first performed Feb 19, 1971. “for Janis [Janis Joplin (1943-1970)]”

How much do we lose, and what do we gain, when we forget to remember why we chose to remember or forget?

This dvar Torah was originally prepared, and offered in a slightly different form, for Temple Micah (DC), 5781.

Handout in PDF and text versions

Full text version of handout for anyone who cannot easily do graphics is posted here.

BACK to TOP