In Torah study with World to Come Twin Cities, one question we considered recently was the difference between reading the Exodus story within the annual Torah cycle and reading the Exodus story in the context of Passover and the seder. We reflected briefly on the festival cycle, which is tied to the seasons and has biblical origins, compared with the Torah reading cycle, established only about 1500 years ago in Rabbinic Judaism. (See, e.g., My Jewish Learning on calendar and Torah reading cycle.) We also talked about how big a role Moses plays in the Book of Exodus, while he is absent from many traditional Passover Haggadah texts — what might that difference imply for our studies and ritual? But mostly we focused on how the weekly Torah readings, beginning in early January this year, can help us prepare for the holiday, which begins on April 1 this year [5786/2026].

Following the WTCTC discussion, I found this teaching from Rabbi Koach Frazier, of Kehillat Sankofa, and thought it worth re-sharing for all interested in beginning to prepare for the season of Liberation.

Healing Rebelliousness

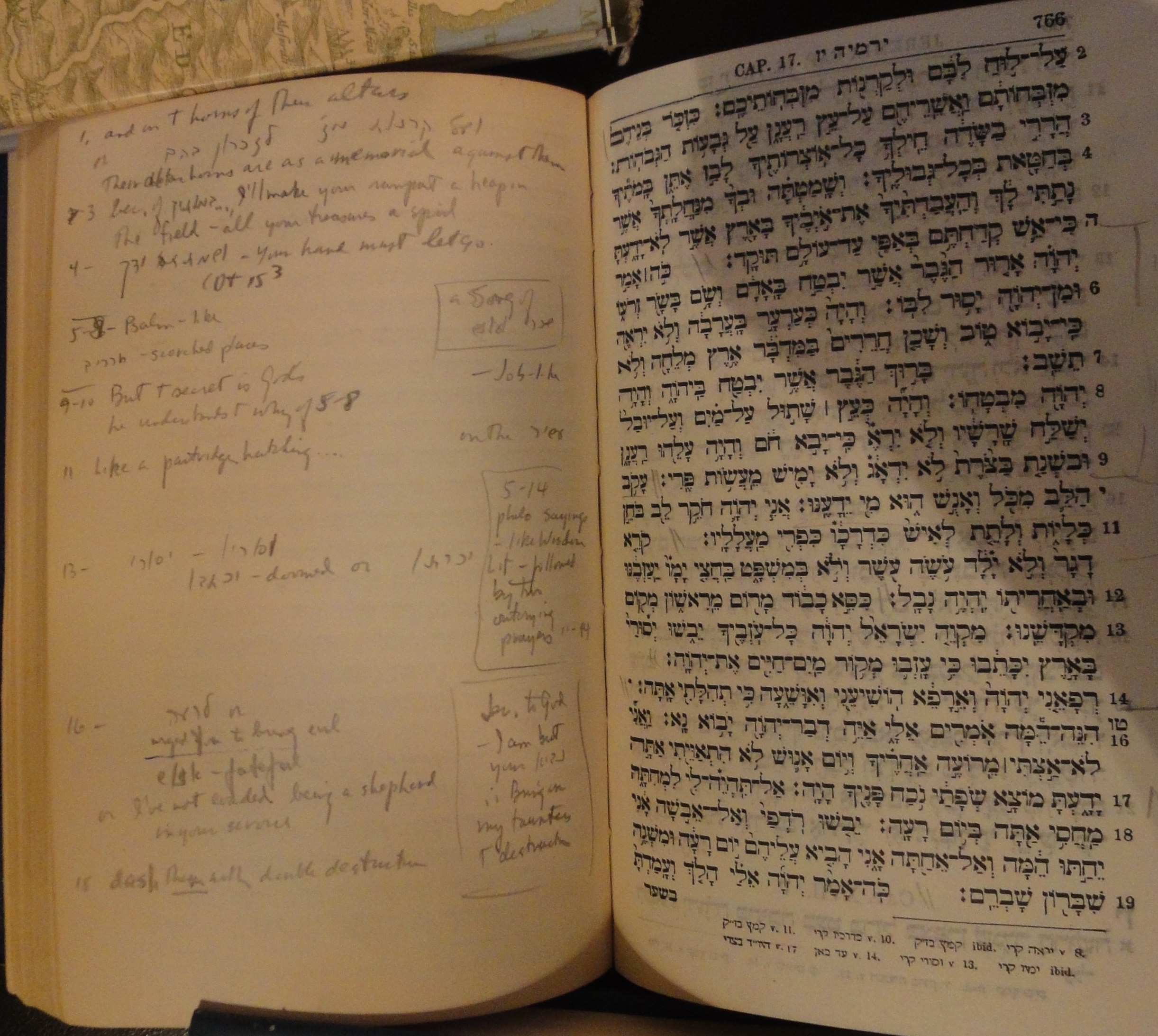

Rabbi Koach’s teaching is based on language in Jeremiah 3:22:

שׁוּבוּ בָּנִים שׁוֹבָבִים אֶרְפָּה מְשׁוּבֹתֵיכֶם הִנְנוּ אָתָנוּ לָךְ כִּי אַתָּה יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ׃

“Turn back, O rebellious [שׁוֹבָבִים, shovavim] children,

I will heal [אֶרְפָּה, er’pah] your backslidings [m’shuvotechem]!

‘Here we are, we come to You,

For You, O ETERNAL One, are our God!– Jer 3:22, JPS 1917-2023 translations

The same expression “shuvu banim shovavim / Turn back, rebellious children,” is found in Jer 3:14. The third word in both spots, “shovavim [שׁוֹבָבִים],” is usually translated as “rebellious” or “backsliding.” It’s spelling — shin-vav-bet-bet-yud-mem — is linked to the first six portions of Exodus:

- שׁ [shin] Shemot (read on Jan 10)

- ו [vav] Vaera (read on Jan 17)

- ב [bet] Bo (read on Jan 24)

- ב [bet] Beshallach (read on Jan 31)

- י [yud] Yitro (read on Feb 7

- ם [mem] Mishpatim (read on Feb 14, 2026)

R’ Koach sites mystics for this teaching (often attributed to “Kabbalists,” but I don’t know a specific citation that is helpful), offering this powerful message for our time:

It’s not the rebellion that is happening in the streets, both here and abroad, against repressive regimes or dictators or would-be dictators. It’s the rebellion we are doing against ourselves and each other, when we don’t participate in teshuva [repair]…

This is a partial transcription of R’ Koach’s Instagram video:

“Turn you rebellious ones’?… It’s not the rebellion that is happening in the streets, both here and abroad, against repression regimes or dictators or would-be dictators. It’s the rebellion we are doing against ourselves and each other, when we don’t participate in teshuva [repair]….

“[For those who think teshuva is done with the high holidays:] We still need to work through our own narrow place…. I guarantee you have harmed someone since Yom Kippur. You might have harmed yourself since Yom Kippur.

“Especially in times of major disruption in our society, in our world, it’s much easier to focus on the violence and the harm that is happening outside. Oftentimes, we are replicating that violence in our homes and communities…. It’s always a good time to do cheshbon ha-nefesh, accounting of the soul, that helps us heal what we have harmed….

“The second half of the verse says that ‘I will heal your rebellion’ — this is about healing ourselves through the work of teshuva. So, let us do the work that is healing ourselves as we move through these six weeks…the internal wok of understanding of where we have been harmed and have harmed, so that we can move outside in a more healed way, instead of replicating that which we are trying to dismantle.”

R’ Koach also notes in his teaching for the portion Vaera that we can understand the plagues as “happening to the power structure, not to the people” and that we can use these weeks before Passover is upon us to generate ideas “of how we are going to be making plague on the system of oppression, not on what is plaguing us.”

— Rabbi Koach Baruch Frazier, via IG for parashat Vaera

With hopes that we can all repair some damage in the next few weeks, in order to avoid “replicating that which we are trying to dismantle,” and learn to be “a plague on the system of oppression”

Join Torah study with WTCTC on Tuesdays or Fridays — https://www.wtctc.org/events