The distance between people and God, and if/how that distance may be bridged, is a major question in theology, philosophy, and the arts, including contemporary Hebrew poetry. The previous post looked at related ways that “touch” [Hebrew: נָגַע] occurs both in Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed and in some verses from Yehuda Amichai. The distance between people and God is explored in a different way in the poetry of Leah Goldberg, according to Rabbi Dalia Marx in “Israeli ‘Secular’ Poets Encounter God.”

Goldberg’s God

Marx’s essay explores three Israeli poets, all considered “secular” rather than “religious,” in order to show that “religiosity and engagement with God are not limited to classical forms of prayer and to ‘religious’ circles.” In addition to Goldberg, poets discussed are Yona Wallach (1944-1985) and Orit Gidali (b. 1974).

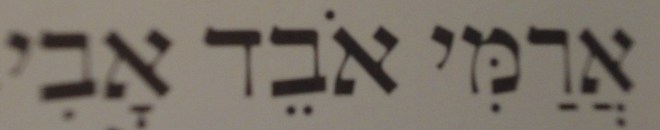

Marx analyzes several Goldberg poems, including the series “From the Songs of Zion.” This four-poem series, Marx tells us, looks at the question raised in Psalm 137: How can we sing God’s song in a strange land? It concludes with “Journeying Birds” (translated here by Marx):

That spring morning

heaven grew wings.

Wandering westward,

the living heavens recited

T’fillat Haderekh: [22]

“Our God,

bring us in peace

beyond the ocean

beyond the abyss,

and return us in fall

to this tiny land

for she has heard our songs.” [23]

— Leah Goldberg IN Marx, pp.188-189

The essay continues:

Unlike Goldberg’s other poems discussed here, “Journeying Birds” reflects no distance from God — who appears like the God of tradition and who is addressed in a heartfelt prayer for a safe journey. Yet the prayer emanates from the mouth of birds, not the poet’s. What is impossible for her, who does not possess the language of prayer, can be uttered freely and naturally by the birds.

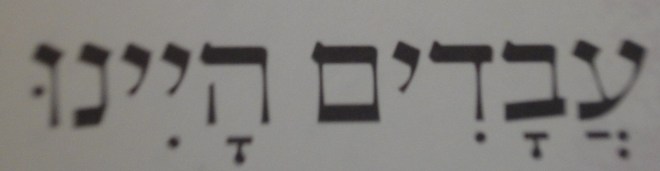

This is not a typical poem for Goldberg in the sense that she uses a familiar liturgical phrase, T’fillat Haderekh, even drawing upon its contents, which, traditionally, asks God “to bring us to our destination for life…and peace…and to return us to our homes in peace.” Like traditional Jewish prayer too, the birds speak in the first person plural [24]. Goldberg, by contrast, could only address “my God,” not the “traditional God” of common Jewish prayer [25].

…Goldberg often writes about birds, who symbolize, for her, joy and freedom. [26]. In this very native and local poem she allows birds to address the ineffable with a joyful prayer that she cannot make herself.

— Marx, “Israeli ‘Secular’ Poets Encounter God,”

IN Encountering God, p.189

The comment above about Goldberg’s use of “my God” refers to two poems also discussed in Marx’s essay: “I Saw My God at the Cafe” and “The Poems of the End of the Journey, 3.” The former does not address God, but describes “my God” in the third person. The latter begins, “Teach me, my God…,” and remains singular and personal throughout:

Teach me, my God, to bless and to pray

Over the secret of the withered leaf, on the glow of ripe fruit…

…Lest my day become for me simply habit.

— Goldberg, from “The Poems of the End of the Journey”

Poems II. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hame’uchad, 1986

NOTE: See Marx’s essay for her translations and discussion of these poems. The full three-part “Poems of the Journey’s End,” translated by Rachel Tzvia Back, appears as a Haaretz poem of the week. (Requires a little patience with ads, but the poem will show up, free of charge).

Tradition and Alienation

In “Poems of the Journeys End,” Goldberg “negotiates with the living God from whom she feels alienated,” Marx tells us: “Traditional prayers are a manifestation of faith; this one is a supplication for faith to arise” (Encountering God, p. 188).

Perhaps it’s a question of chicken and egg, in terms of who picks up a siddur in the first place. But traditional prayers, in contrast to Marx’s declaration, are filled with words and imagery meant to spark a prayerful attitude…a sense of faith, one might say, which the siddur does not take for granted. (Imagining that we are imitating choruses of angels, joining our voices with “all living things who praise,” outright begging God to “open our lips.”)

Moreover, far from being new or unique in Goldberg’s poem(s), a feeling of distance or alienation from God is a major theme in the Book of Psalms. The Jerusalem Commentary on Psalms, e.g., includes a category called “descriptions of the spiritual distress of the psalmist, who feels himself far away from God” (p.xxiii).

It seems hard to believe, in fact, that Goldberg’s “Poems of the Journeys End” is not in active in dialogue with these themes in the psalms:

And he shall be like a tree planted by streams of water,

that brings forth its fruit in its season, and whose leaf does not wither;

and all that it produces prospers.

— Psalm 1:3

So teach us to number our days, that we may get us a heart of wisdom.

— Psalm 90:12

But, somehow, her poetry seems to be read as oddly disconnected from the tradition that helped forge it:

As the orison of an ever-receding horizon, Lea Goldberg’s poems blur the line between the secular and religious divide. They reach for a “contiguity” (Dan Miron’s term) between tradition and a breach with that tradition, awakening anew the religious power of the Hebrew language. And so, this volume of poetry speaks uniquely to this generation of Jewish readers. It should be kept by one’s bedside, read as meditations, “blessings” or “hymns of praise” each morning and night, just as God renews Creation each day (Psalms 104), in the glory of dappled-things, a “withered leaf” or “ripe fruit”, reviving “all things counter, original, spare, and strange” (Gerard Manley Hopkins, “Pied Beauty”), so that your words do not blur in vulgar gibberish, so that your days not turn mundane.

— Rachel Adelman, 2005 review of a Goldberg volume

Hers? Mine? Ours?

Psalms are an odd hybrid of poetry and prayer. It’s not clear where they would fall when Marx declares, in “Israeli ‘Secular’ Poets Encounter God,” that prayer and poetry share an affinity but differ in essentials. But it seems odd that Marx makes so much of Goldberg’s shift from first-person singular to plural in the three poems discussed, without even mentioning that the psalms also include first-person singular and plural language, for both narrator and address to God.

Marx concludes her essay by reiterating the hope, expressed by poet Avot Yeshurun, that “Hebrew literature should renew prayer.” And she does make her point that ‘secular’ poets participate in a “vivacious religious sentiment…far richer and more bountiful than initially expected” (Encountering God, pp.196-197). But her decision to contrast poetry with “traditional prayer,” without mentioning psalms serves to dissociate Goldberg’s work from its background.

Psalms have, it seems, been considered somewhat old-fashioned for millenia —

When the sages in the Second Temple period composed the prayers and blessings that all Jews are obligated to recite, they created new texts rather than selecting chapters from Psalms….The main reason for this tendency seems to have been that the psalms were written in an ancient poetic style not easily understood in the Second Temple period. The rabbis used a style similar to the spoken language of their day, so that ordinary Jews could understand them.

— Jerusalem Commentary on the Psalms, p. xliii

— but also demand their own renewal: “Sing unto the LORD a new song” (Psalm 149:1).

Goldberg’s “withered leaf” and desire to avoid the mundane are a fine example of renewing an old theme — except when authors, like Adelman, fail to mention the theme being renewed.

NOTES

“Israeli Secular Poets Encounter God” by Rabbi Dalia Marx

IN Encountering God: El Rachum V’chanun: God Merciful and Gracious. Lawrence A. Hoffman, editor. Woodstock, NY: Jewish Lights, 2016

Full paper also posted on Academia

TOP

Marx’s end-notes:

22. T’fillat Haderekh (literally, “the Road Prayer”) is the title of the traditional prayer for beginning a journey.

23. Leah Goldberg, Milim Achronot (Last Words) (Tel Aviv, 1957) reprinted in Poems II, 221 (my translation, DM).

BACK

24. Talmud, Berakhot 29b

25. For another exception, see Amir, “Prophecy and Halachah,” 52-53.

[Yehoyado Amir, “Prophecy and Halachah: Toward Non-Orthodox Religious Praxis in (Eretz) Israel. Tikvah Working Paper 06/12 (New York: NYU School of Law, 2012)]

26. Lieblich, Learning about Lea, 237

[Amia Lieblich, Learning about Lea (London: Athena Press, 2003)]

BACK