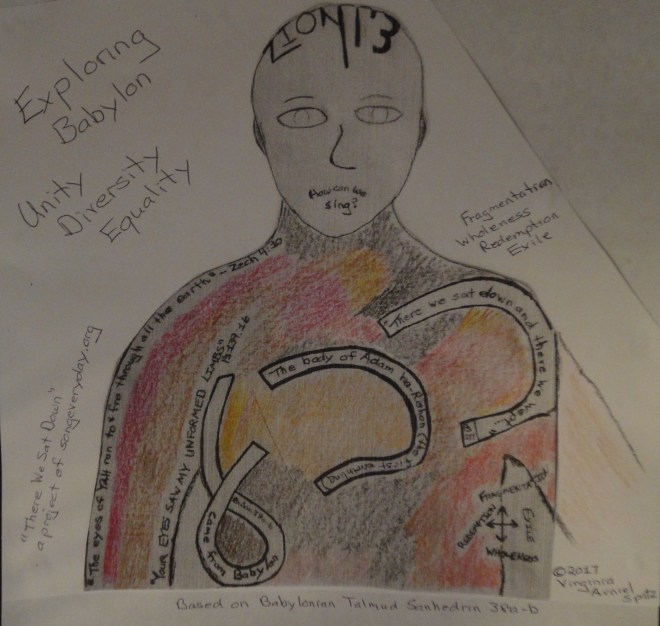

Exploring Babylon: Chapter 3.1

The Hebrew “Bavel” is translated into English as “Babel” in Genesis and as “Babylon” when it appears elsewhere in the Tanakh. Bavel as Babel shows up in a total of two verses in the entire Torah text: Gen 10:10, Nimrod’s legacy — “the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar,” and Gen 11:9, the close of what is usually called “The Tower of Babel” story. Bavel, now Babylon, is not mentioned again until 2 Kings 17:30, during the exile of the northern kingdoms.

After that, the Concordance (Even-Shoshan 1998) lists 281 additional appearances Bavel in the prophets and two in Psalm 137. Down the road, we’ll explore Babylon references in the later Tanakh. For now, let’s return to the Genesis.

Babel and Babylon

Jewish commentary on Gen 11:1-9 often treats the Bavel of Genesis as a place apart from history and geography. The focus is on the Babel tale’s placement in the Torah: after the Flood — when Noah’s descendants were told to “be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth” (Gen 9:1) — and before Terah, Abraham, Sarah, and Lot leave Ur (Gen 11:31). Babylon is far in the background, often unremarked.

For example, Rabba Sara Hurwitz, of Yeshivat Maharat, recently shared a lovely, powerful dvar torah for the Torah portion Noach (Gen 6:9-11:32):

And God models how to exist in a world of diversity. In verse 7, when God goes down to mete out their punishment, God says: “Come let US go down.”

Rashi, addressing the question of who God is talking to, suggests that God “took counsel with the Angels, with his judicial court.” Surely God knows how to mete out judgment and punishment, as he has already done unilaterally in the Torah without discussing it with the Angels? Perhaps, God turns to them to asses their thoughts on the sin of the people, to hear their opinion, to debate the pros and cons of scattering the people all over the world. By addressing the Angels, God models how to collaborate with others. Diverse ideas, when debated in a respectful manner, can lead to growth, greater productivity, and ultimately harmony.

…The challenge with diversity is to reject the tendency toward segregating, and running away from conflict. For out of conflict, when we are willing to confront one another with healthy debate, tolerance is born…

— Hurwitz, ָ”Harmony, not Conformity”

Hurwitz’s dvar torah is about Babel, not Babylon. She mentions no historical city or empire. Plenty of homelies, in- and outside the Orthodox world, identify Babel with Babylon and incorporate views of the latter; idol-worship, smugness of place, and failure to follow God’s commandments are common themes linking Babel and Babylon. However large a role Babylon plays in any given dvar torah, the overarching point is to help us better understand the Torah, ourselves, and our obligations as Jews — not to tease out insights on life in ancient Babylon.

Still, Jewish bible study has long examined the relationship of the historical, geographical Babylon to the Babel of Genesis 11. For thousands of years, that discussion has returned again and again to concepts of unity and difference, centralizing and dispersing. And for thousand of years, intentionally or not, those discussions have incorporated political ideas about these themes.

Because Babylon, in its many guises, is never far away from Jewish consciousness. Remember: We’ve already found Babylon in the primordial stuff of Creation and in the formation of the first earthling….

It’s Complicated

Erin Runions analyses Babylon as a complex, often contradictory, theme in U.S. culture and politics. From a non-Jewish academic perspective, she writes about the Tower:

The Tower of Babel appears in political and religious discourse when people want to think about what holds the United States together in the face of its racial and cultural diversity. Because the Babelian creation of diverse languages is typically read as both God’s will and at the same time a punishment, the story lends itself well to representing a range of attitudes about difference. A confusing ambivalence about unity and about too much diversity emerges. Via the Babel story, Babylon is sometimes used to promote tolerance toward sexual and ethnic difference, insofar as U.S. Americans see themselves as benevolent toward difference. At other times it is used to stigmatize and attack difference as embodying a problematic unity without moral distinctions.

— The Babylon Complex: Theopolitical Fantasies of War, Sex, and Sovereignty (NY: Fordham University Press, 2014), p. 22-23

Runions calls Babylon “a surprisingly multivalent symbol” in U.S. culture and politics and then dedicates 300 pages to unpacking its complexities. Much of The Babylon Complex is outside the scope of this blog’s project. But Runions’s work illuminates how the surrounding culture understands and uses the concept of Babylon — and those insights are crucial, however tangential.

We’ll explore The Babylon Complex further another day. For the moment, let’s return to Rabba Hurwitz’s image of God modeling “how to collaborate with others” and add a postscript.

Different Folks

This past week, Playing for Change re-shared this video — one of my favorites among an enormous menu of great, community-building music. Sly Stewart’s great lines —

You love me

you hate me

You know me and then

Still can’t figure out the bag I’m in

seem so appropriate to this stage of #ExploringBabylon and Hurwitz’s charge to us.

Plus: Who doesn’t need hundreds of children singing and dancing to Sly and the Family Stone’s “Everyday People”?!

More here for those interested, about TurnAround Arts and Playing for Change.