I read Dr. Seuss when I was little. I poured over the illustrations in Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses, although I don’t recall caring much for its verses. If my household discussed poetry at all it was most likely a piece of doggerel in a Mike Royko column (Chicago Daily News then).

I do remember being struck by “We Real Cool,” by Gwendolyn Brooks (1917 – 2000), when it was introduced to us at school. But we were given to understand that this was not “real poetry,” which only lessened my faint interest in the topic. Any connection between Bible and poetry only added, for both literary genres, further impenetrability.

I meant by “impenetrability” that we’ve had enough of that subject, and it would be just as well if you’d mention what you mean to do next, as I suppose you don’t mean to stop here all the rest of your life.

— Humpty Dumpty to Alice, Alice Through the Looking Glass

“Real Poetry”

Later schooling didn’t improve my relationship to poetry, and I avoided it pretty successfully in college….except for my forays into writers’ groups, where I continued to find poetry a foreign, and often self-absorbed, form of expression. I did come to enjoy authors like Adrienne Rich, Marge Piercy, and Alicia Ostriker. But I think my early training stuck, so that I somehow classified this as outside the realm of “real poetry.”

When, nearly fifteen years ago, I began studying the poetry of Yehuda Amichai, it was with the intention of improving my Hebrew and for the connections, in Open Closed Open, to the prayerbook. I was convinced I didn’t like poetry and/or that it was somehow beyond me.

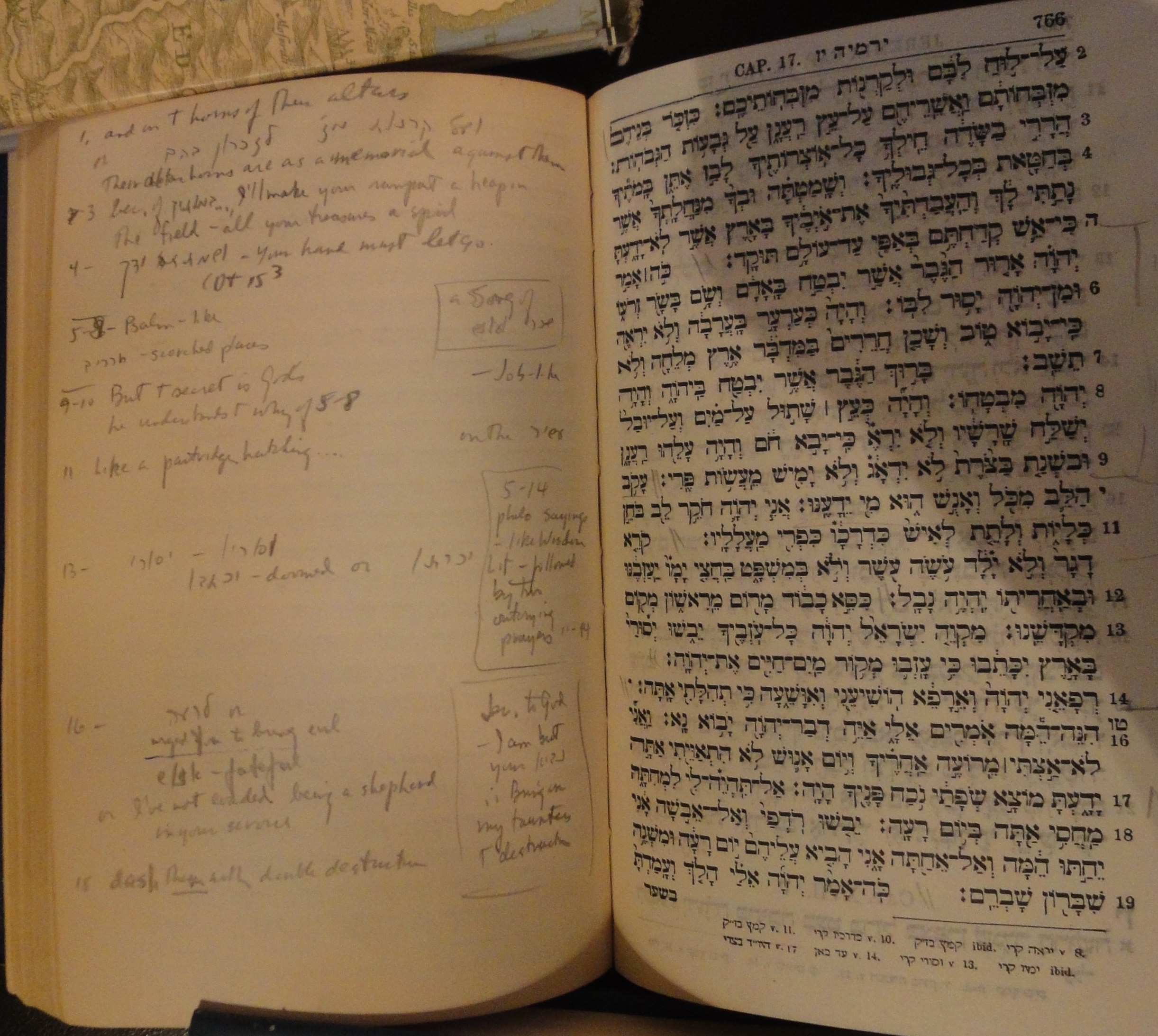

Attempting to read poetry in a language that is foreign to me proved fortuitous in that it taught me how hard poetry is to translate — and, therefore, some of the power poetry can convey. Plugging along word-by-word forced me into looking carefully at the language, much more carefully than I generally do when reading my native English. Eventually, I became a sort of convert to poetry as a means of expression and started to investigate the field as it suited me and whatever poem I was exploring.

All of this is to say that I have zero credentials for understanding poetry in general or Hebrew poetry in specific. I do spend a lot of time with the Hebrew Bible, but, again, without any formal training. Whatever I’ve learned is pretty haphazard. I don’t think I’m the only one who was taught some unhelpful things about “real poetry,” however, so I share what I’ve found hoping it’s of use to others….

Africana Perspectives and Fortress Press

As the annual Torah cycle brings us soon to the Song of the Sea, I recommend “Zora Neale and the Lawgiver in Conversation: Exodus 15 and Moses: Man of the Mountain” by Hugh R. Page, Jr. This piece appears in Israel’s Poetry of Resistance: Africana Perspectives on Early Hebrew Verse (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2013), an unusual volume combining the author’s personal essay and poetry with theological discussion:

At that time Moses and the Israelites

Sang this song about YHWH.

Here are the words:

…My power is in Jah‘s song,

Surely, He is my salvation.

He is indeed my god.

That is why I praise him.

He is my ancestral god.

Therefore, I extol him.

— Page, Israel’s Poetry of Resistance, p.21

Page’s use of “Jah” here, he explains, is part of a “conscious effort to bring these biblical poems into more direct conversation with contemporary Africana music that articulates spiritualities of resistance…” (ibid, p.27). Throughout the book, the author focuses on how biblical poems disrupt their “textual surroundings,” and how that helps foster a theology that can work to “resist and dismantle exploitative institutional structures” (ibid., p.26).

Page summarizes his argument for pursuing ancient Hebrew poetry:

Early Hebrew poetry gives us ready access to the spiritual musings of some of our ancient Jewish spiritual forebears….It shows us the role that poets and poetic language played in shaping our conceptions of the divine and our understanding of how God’s self-disclosure to humanity unfolds. It forces us to deal with the symbolic nature of theological and poetic language and asks that we stretch ourselves intellectually as people of faith.

— ibid, p.129-30

I originally found this book while exploring various aspects of exile and life in Babylon. I am enjoying it differently at this juncture. Here’s more about the book, including a link to sample pages.

Fortress, by the way, is a Christian press established in 1962 offering some important, intersectional perspectives on bible reading. Here is a little more about them and their 2010 Peoples’ Companion to the Bible.

Medieval Poetry

When my study partner and I were seeking some new text, with a new perspective, I consulted an old teacher, Diana Lobel. She offered a number of suggestions, including The Gazelle: Medieval Hebrew Poems on God, Israel and the Soul by Raymond P. Scheindlin (NY: Oxford University Press, 1991). We are working our way through this volume, reading poems by Judah Halevi, Solomon ibn Gabirol, Moses ibn Ezra, with Scheindlin’s literary and theological commentary on each one.

The poems are provided in Hebrew, with English translation as well as additional linguistic commentary. Beyond the individual poems and their exegesis, Scheindlin’s book highlights ways in which Arabic and Hebrew traditions are interwoven and build upon each other. We have found The Gazelle helpful in considering questions about literary borrowing and adaptation, assimilation, and preservation of minority culture.

I have found studying these poems instructive in unlocking some of the mystical imagery in the work of contemporary Israeli poet, Rivka Miriam. I am sure we will continue to see resonance of these medieval works in other Hebrew poets, as well as in music.

Seeking more background, I stumbled upon this Medieval Hebrew Poetry website. [Archival link] Henry Rasof, who created the site as part of his master’s thesis from Gratz College, is a poet in his own right as well. UPDATE 1/6/25: Seeking to update links, I discovered that Henry Rasof passed away in 2022. He had been seeking a new editor to take over the site, back when, but no one stepped up. Rasof, z”l, said then that he discovered the topic late in life “and has since been bitten by the bug” — just in case a reader has been bitten by a similar bug or knows someone interested in a new project. Here is an archival link to Boulder Jewish News with Rasof’s posts.

Modern Poetry — and a Sale!

Amidst an effort to reorganize this blog, some of the resource pages were sort of misplaced. While I work to sort that out, I posted some poetry-related resources, focusing on contemporary Hebrew poets.

And, in the process of updating some of that information, I discovered that Wayne State University Press — which publishes The Modern Hebrew Poem Itself, among other related resources — is offering 40% everything until January 11.