Robert Alter completed an amazing project. His translations of the Bible continue to offer new, sometimes more literary, possibly more “accurate” renderings of the text. But scholars everywhere seem blinded by the sheer number of pages just published or otherwise befuddled into teaching falsehoods and half truths.

Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, for example, offered a ten-minute ode to Alter’s translation as a commentary to this week’s Torah portion (parashat Bo: Exod 10:1-13:6). Here’s his podcast, “What is Lost in Translation.” In praising Alter, however, he manages to inadvertently dismiss the work of his own movement.

Darkness and Light

Toward the end of the podcast, Jacobs focuses on one phrase in Alter’s translation and commentary:

“‘…that there be darkness upon the land of Egypt, a darkness one can feel.’

…but all the Israelites enjoyed light in their dwelling places.”

a darkness one can feel. The force of the hyperbole, which beautifully conveys the claustrophobic palpability of absolute darkness…

— translation/commentary on Ex 10:21, 23 from The Five Books of Moses. (NY: Norton, 2004)

Jacobs cites this material as though it were new, although Alter published this translation and commentary in 2004. More importantly, I think, Jacobs fails to note that Alter’s English differs very little from the older translations widely available for decades — in fact, some published by his own Union for Reform Judaism.

Here, for comparison are Jewish Publication Society versions of the last century:

“‘…that there may be darkness upon the land of Egypt, a darkness that can be touched.’

…but all the Israelites enjoyed light in their dwellings.”

— “New JPS” translation (Philadelphia: JPS, 1985)

“‘…even darkness which may be felt.’

…but all the children of Israel had light in their dwellings.

— “Old JPS” translation (Philadelphia: JPS, 1917)

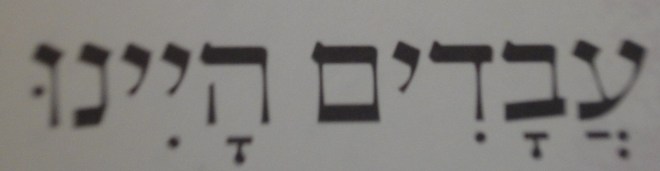

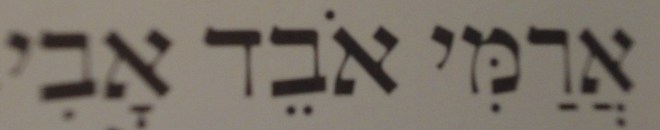

Alter’s “a darkness one can feel” is slightly pithier and so somewhat stronger — and as Jacobs notes, closer to the more succinct** Hebrew, v’yamush, hoshekh [וְיָמֵשׁ, חֹשֶׁךְ] — than the JPS versions. But Alter’s “in their dwelling places” for b’moshevotam [בְּמוֹשְׁבֹתָם] is slightly longer than “in their dwellings” of the JPS. So, I’m not sure that, in this particular set of verses, the differences are worthy of great note, all told.

King James and Robert Alter

Jacobs, like a number of others commenting on Alter’s work, compares Alter’s work to the King James Version. (Maybe they’re all reading the same press release?) But Jews and Christians have been translating the bible for many generations since 1611, and all innovation since then is not attributable to Robert Alter, no matter how amazing his recent accomplishment. The weirdest — and, I feel, saddest — thing about Jacobs’ praise for this particular verse of Alter’s translation is that his podcast could just as easily have cited a ten- or twenty-eight-year-old publication from the URJ itself:

- The Torah: A Women’s Commentary (NY: URJ Press & Women of Reform Judaism, 2008) uses modified “New JPS” language, including the verses as cited above;

- the 2005 URJ version, which I don’t happen to have handy, also uses JPS;

- the 1981 The Torah: A Modern Commentary, from UAHC [now URJ], uses a mid-century version of the JPS translation, with the exact language quoted above.

…This is not to say that Alter has not provided new and interesting perspectives or given us some beautiful new language to help us appreciate the Hebrew original. But I fear that what really is new and interesting in Alter’s work is being lost in all the repetition of tired nonsense, false comparisons, and outright omissions in discussing his work.

Moreover, it seems truly dangerous, given the current state of government and journalism, to share information in ways that might mislead and to teach in ways that fail to provide context for “new” ideas….

A final quibble with Jacobs’ podcast: He makes a point of noting that Robert Alter (b. 1935) is in his 80s now, as he completed this huge project. If we’re going to stress the author’s age and/or the number of years he worked on the project, however, let’s be accurate. Alter was not yet 70 when The Five Books of Moses was published, and he was in his early 70s when his Book of Psalms (Norton: 2007) came out. Again, not to say it’s NOT an accomplishment to translate the Torah or the Psalms at 70 or for an individual to complete a bible translation at 83 — or any age! Just that we cannot be re-writing history by inattention to facts.

Note on the 2018 W.W. Norton Publication

A note about these books as books: While I remain in awe of Alter’s scholarship and literary merit, I am deeply disappointed in this three volume set ($125). The set does offer new material, particularly in the Prophets. But there is no new introduction to the Bible as a whole, and there is no additional commentary on the completion of the project; in fact, each of the three volumes repeats verbatim the same introduction to the Bible and its translation that appeared in Alter’s Five Books of Moses in 2004!

If this picture is clear enough, and you’re really curious, note that the section numbering differs in the two volumes, because the section specific to the Five Books was moved.

Final plea to scholars: I would personally appreciate, as I’m sure would many others, a review or analysis of the recent publication which actually addresses specifics — in organization and layout as well as in content — with a focus on what is actually new in 2018.

Post updated 1/13/19: mostly in formatting, correction of a few typos; also addition of citation to UAHC 1981 Torah (above) and plea here. See also, “Found through Alter’s Translation,” further to this discussion, posted on 1/12/

NOTE:

**In the podcast cited here, Jacobs also compares Alter’s translation of Psalm 23 with that of the King James Version, focusing on the darkness phrase relevant to Parashat Bo. Alter’s “vale of death’s shadow” is more direct than the KJV, “valley of the shadow of death,” while maintaining the connection with death — which some newer translations lose:

valley of deepest darkness — JPS 1985

darkest valley — New International Version (1973-2011)

valleys dark as death — American Bible Society, 2006

dark valley of death — God’s Word, 1995

Do note, for clarity of record, that Alter’s translation and commentary on the Book of Psalms was published in 2007.

BACK

A parallel situation still applies all too well in much of the Jewish world. As does his analysis of how well-intentioned attempts at diversity and inclusion often fail to create real change. Many of his recommendations for the Church are ones other faith communities should explore as well:

A parallel situation still applies all too well in much of the Jewish world. As does his analysis of how well-intentioned attempts at diversity and inclusion often fail to create real change. Many of his recommendations for the Church are ones other faith communities should explore as well: